The Dragonslayer and His Sword: Gazing into the Abyss of Social Networks [en/cn]

- Published on

Chinese version is available here.

Reality is merely an illusion, albeit a very persistent one. – Albert Einstein

Back in high school, like most teens, my life pretty much revolved around schoolwork, sports, and dating. I was noticeably out of the loop when it came to the goings-on in my class, cram school, our own school, or neighboring schools. It wasn't until the summer vacation of my sophomore year, as a camp was winding down and group members were exchanging contact info, that I even learned about something called Facebook. It was wild—you could message people without paying for texts, share photos and updates, and see what everyone was up to. I still remember the thrill of diving into this new world: on my blue Acer laptop, logging into Facebook and seeing a group photo from the camp with my name tagged. I could comment, like, and share it on my own page. My camp buddies set up a group chat, and we were all chatting away, sharing our thoughts and lives, hoping to meet up again someday. It felt like the camp never really ended. (Of course, that excitement faded pretty quickly. There’s always something new to chase when you’re young, and looking back isn’t really a thing.)

History is full of these dramatic moments: a random day that seems just like any other, but a single idea or choice flips everything on its head for generations to come. In 2008, the young Mark Zuckerberg probably had no clue that his little side project would end up reshaping society as we know it. Love it or hate it, social media platforms like Facebook, Instagram, Reddit, Twitter, and TikTok have completely transformed how we communicate, connect, organize, and collaborate—and they did it in record time.

For those born into the internet age, this shift might be hard to spot, but for folks like us—who lived through the switch in how we use the web, caught between two eras—it’s a stark and profound change. We didn’t just witness the birth of something new; we also saw it fling open Pandora’s box, unleashing a flood of problems, all fueled by capital.

The Clear-Cut / First-order effects

- Attention Economy and Addiction: When social platforms primarily run on an advertising model (ads often account for over 90% of revenue), the variables determining ad value boil down to the quality of user attention, audience purchasing power, and market supply and demand. And the most crucial of these, "attention quality," is essentially the degree of user engagement—or addiction. Thus, algorithms on various platforms are designed with the objective function of "maximizing user engagement," leading to the digital addiction phenomenon we're all too familiar with today.

- Fake News and Misinformation: This mess comes from a twisted ad model. Sensational, over-the-top content grabs attention better, so algorithms amplify it. Besides, as the saying goes, "a lie can travel halfway around the world while the truth is putting on its shoes." This inherent asymmetry gives rumor-mongers a perfect environment to spread fake news. Couple that with a prevalent modern attitude of nihilism towards truth, and the problem becomes even more intractable.

- Cyberbullying and Hate Speech: Think of a character from a Japanese drama: a guy who’s a pushover at work, bowing to bosses and clients, but a total dictator at home with his wife. That split personality isn’t uncommon. While the internet isn't exactly a lawless land, a certain degree of anonymity has allowed a culture of trolls and armchair critics to flourish. Everyone suddenly fancies themselves an expert, like the stereotypical cab driver: armed with a middle-school education but brimming with overconfidence, they have a theory for everything from astronomy to geography, always feeling their fiscal policy would be more effective than the central bank governor's. And that's not even mentioning the destructive power this trinity – overconfident crowds, waving the banner of justice, and supercharged by attention-grabbing algorithms – can unleash.

- Data Breaches and Privacy Leaks: When personal data is seen as a valuable asset, databases holding vast amounts of user information become like well-known, glittering gold mines, naturally attracting a swarm of gold-diggers—aka hackers. What's more serious is that personal data leakage has two unavoidable asymmetries: (a) leaked information is a one-way street; it's incredibly hard to undo the damage; (b) the entire system's security is only as strong as its weakest link. Even if most parts are secure, one weak spot—like a sloppy government agency or telecom—can tank privacy for everyone.

- The Right to Leave: When users get fed up with a platform—whether due to its policies, algorithms, or design—it's actually quite hard to truly leave. Quitting means ditching all your posts and your entire social web—your “social graph”—which makes leaving feel like a trap.

The Less Obvious / Second-Order Effects

- Echo Chambers and Polarization: Algorithms are all about attention, and attention means feeding users what they like. Comfort zones are cozy by design, and let’s be real—most people don’t want to leave them for long. That naturally leads to echo chambers and polarization. Whether this is good or bad is a hot topic for debate. Recently discussed concepts like Plurality, Tribalism, and Squad Culture might just be a Renaissance-like response to this phenomenon.

- Damaged Democratic Resilience: Even more seriously, social media erodes democracy’s foundation. When fake news floods the scene and truth becomes a wild goose chase, people slip into cynicism and apathy. Truth stops mattering, and we can’t even agree on what’s real anymore—just watch “Don’t Look Up” and you'll get it. That’s a dictator’s dream: when there’s no shared basis for truth, beauty, or goodness, lies, ugliness, and evil blend right in.

Why are people talking about deSocial again lately?

Ever since social networks took off, they've been a hotbed for entrepreneurs (and a never-ending source of material for Facebook to copy, lol). Back in the early 2010s, plenty of attempts were made to tackle the problems posed by centralized social platforms using different technologies and designs. For instance:

- App.net : A variation of Twitter (sorry, it'll always be Twitter to me), initially designed to ditch ads, avoid selling user data, and allow developers to freely extend platform functionality through an open API. However, even though users craved more privacy and autonomy, very few were actually willing to pay for it, making it tough for App.net to stick around.

- Diaspora : A social network where users run their own nodes (called "Pods"), promising users complete control over their data and privacy. It emphasized no single point of failure, allowed for anonymity and pseudonyms, and championed community governance and an open-source ethos.

- Path : A platform that initially capped friend counts at 50, trying to foster deeper, more meaningful connections through tighter-knit social circles.

- Peach : A platform that deliberately excluded algorithmic feeds and hashtags, aiming to help users break free from the "attention rat race" and focus on pure human interaction.

Revisiting these past attempts isn't the main focus here, but they do provide the context: many of the dilemmas social networks face today are hardly new, and people have been trying to come up with solutions for a long time. History doesn't repeat, but often rhymes. Many ideas that seem brand new today were actually floated long ago; it's just that the tech back then wasn't mature enough to make them a reality – think of the "computer" in the 19th century, "flying cars" in the 1910s, or "artificial intelligence," first proposed in the 1950s. Now, as new technologies come of age, many ideas once considered way ahead of their time are being dusted off and revisited, and the current buzz around "decentralized social" (deSocial) is an example of this. These new generations of dragon-slayers, sharp-eyed and proud, are ahead of their generation in seeing the potential to forge a truly effective dragon-slaying sword.

The new materials for forging this next-gen dragon-slaying sword can be broadly categorized into three types:

- Blockchain: A hard material for building networks. Some use it for storage, some as a timestamping service, and others engrave identities onto it.

- Programmable Cryptography: A toolkit of privacy-preserving "magic spells," primarily including Zero-Knowledge Proofs (ZKPs), Fully Homomorphic Encryption (FHE), and Indistinguishability Obfuscation (iO).

- Decentralized Web (dWeb): Older communities and tech stacks, encompassing Peer-to-Peer (p2p) technologies, Distributed Systems, and Decentralized Storage (dStorage).

How to define deSocial?

Trying to define deSocial directly through its technical characteristics usually leads to a lot of confusion. On the surface, platforms claiming to be decentralized often use one of the following traits:

- They allow users to log in via crypto wallets, skipping traditional Know Your Customer (KYC) processes;

- User-generated content is uploaded to some form of distributed storage, making it harder for content to be unilaterally deleted;

- And interactions between users are recorded on a blockchain, often in a compressed format (like hashes), to ensure their uniqueness and verifiability.

However, this "tech-driven" definition quickly sparks even more questions, such as:

- If the content is uploaded to a relatively centralized chain (take BSC for example), does it still count as decentralized?

- Exactly what data gets uploaded to distributed storage? And can users easily retrieve their own data from these storage solutions?

- If the platform shuts down, can users take these interaction hashes and migrate to a new server, recreating those relationships?

These questions highlight the obvious limitations of defining decentralized social purely by its technical implementation. The term "decentralization" itself is vague and has multiple meanings, and social networks involve many dimensions like identity, data storage, content curation, and community management. So, approaching it from a technical standpoint, you're bound to miss the forest for the trees. The truth is, technology is ultimately just a tool, not the end goal itself.

Perhaps a better approach is to work backward: first, pinpoint the elements in current social platforms that users find genuinely frustrating. Then, by looking at these negatives, deduce the ideal qualities we're truly after. Only then should we circle back to examine to what extent current technology can actually deliver these features, and what the trade-offs or costs of implementation would be.

To borrow the concept of coordinate axis transformation, it's like shifting from a 3D space defined by technology to a 3D space defined by the features end-users actually want:

- User Sovereignty & Privacy: Users want more control over their accounts and data, whatever that specifically means. Beyond not wanting their hard-earned accounts to be unilaterally shut down at any moment, this usually includes more nuanced privacy protection, the ability to freely export and back up data, and portability for their identity and social graph. Privacy protection often involves programmable cryptography, while content and data frequently rely on solid APIs or deStorage. Identity and social graphs, in turn, can be linked to Self-Sovereign Identity (SSI), Decentralized Identity (DID), and Digital Identity Wallets (DIW).

- Content Freedom & Algorithmic Transparency: Users are looking for more transparency and choice in content curation, wanting to break free from the manipulation of commercial algorithms and regain control over their attention. Content censorship, fake news, and AI-generated spam are all massive problems, and they often present a dilemma. For instance, if a completely uncensored platform appears child pornography or content selling firearms and drugs, how can it ensure compliance? Besides attempting to establish open-source, transparent algorithms with credible neutrality, another pragmatic and valuable approach is to offer a choice of multiple algorithms. Blockchain has the potential to provide credible neutrality, while decentralized network technologies can offer customizability.

- Open Source & Composability: If you’ve ever spotted the cheeky “link in the comments” trick, you’ve seen how today’s social platforms are walled gardens—digital autocracies that keep information from flowing freely. Leaving aside users' fundamental rights, this closed-off nature stifles the potential for emergence. Even with simple elements, sufficient openness can unleash users' creativity, making a digital world more engaging and fun. For example, players creating electronic circuits, "thunder-trapping" Mickey Mouse, or pulling off all sorts of creative maneuvers in The Legend of Zelda, or building entire civilizations in Minecraft are all testaments to this. Technically, using blockchain-based Hyperstructures as foundational building blocks provides inherent composability, with Autonomous Worlds being one of the most cutting-edge experiments in this area. If permissionless systems aren't strictly necessary, then APIs developed in an open spirit, or setting core components as open source protocols, can also significantly enhance composability and innovation.

Back to the dragon-slaying sword metaphor: just as alloys are created by mixing different elements to achieve properties superior to any single metal, in practice, technological components are often mixed and matched to solve specific problems. For instance, AnonCreds combines DID and ZK; Filecoin merges dStorage, Blockchain, and ZK; and Tornado Cash blends ZK with Blockchain.

Finally, it's worth noting that SocialFi, in my view, seems more like an overlay of blockchain's financial functions onto traditional social networks, without genuinely addressing the core issue of decentralization. Marx reminded us that the base shapes the superstructure: if the foundation isn’t truly decentralised, a fancy financial layer won’t spark a real social reboot. Imagine Facebook minting every post as an NFT and letting users tip in stablecoins—if it doesn’t move the needle on the three dimensions above, it’s still a centralised product wearing decentralised paint.

Approaches of Existing Products

Using the framework above, let’s look at some well-known decentralised social projects and see which path each one has chosen—and how they actually answer the three big questions.

Farcaster

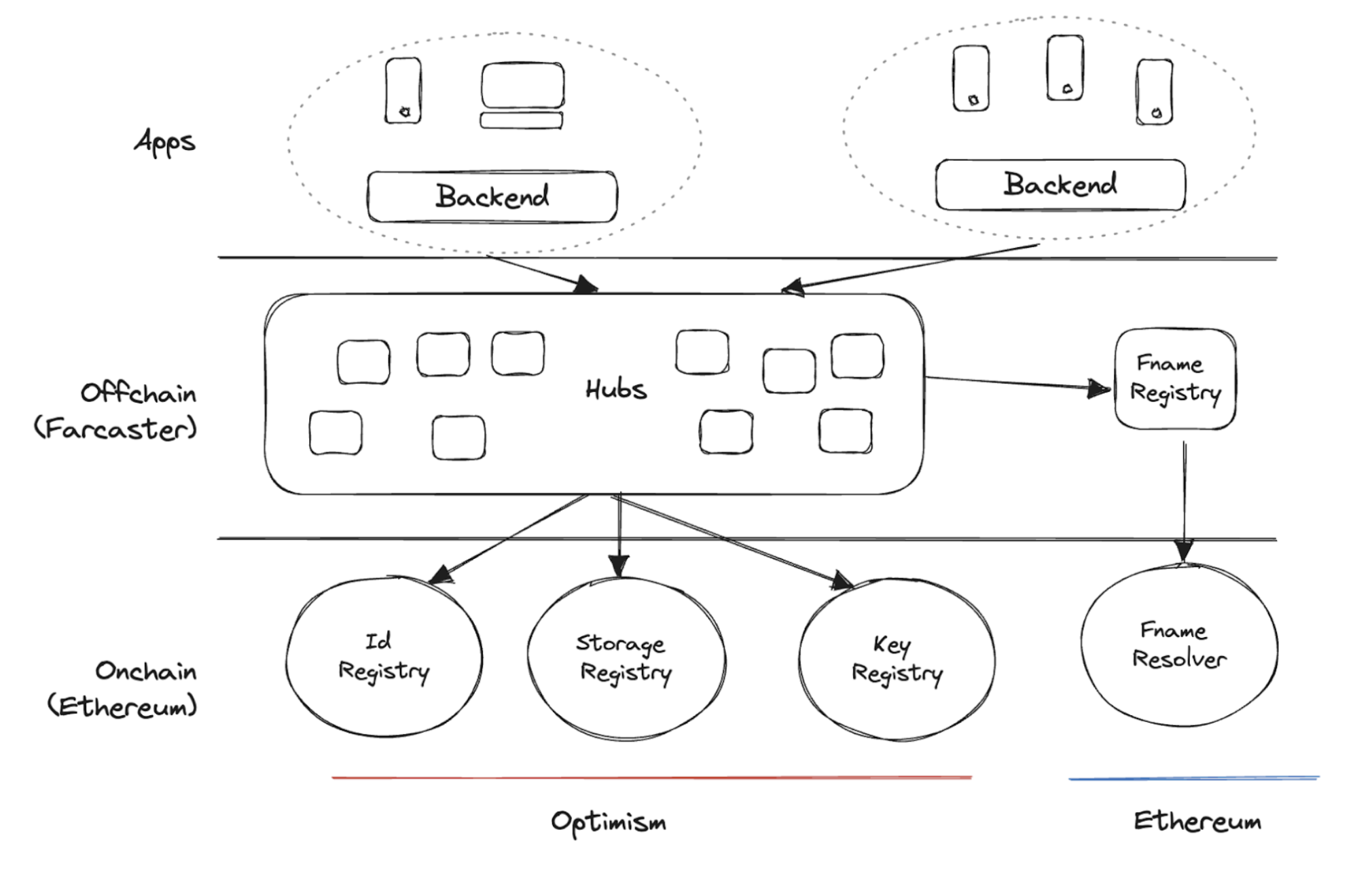

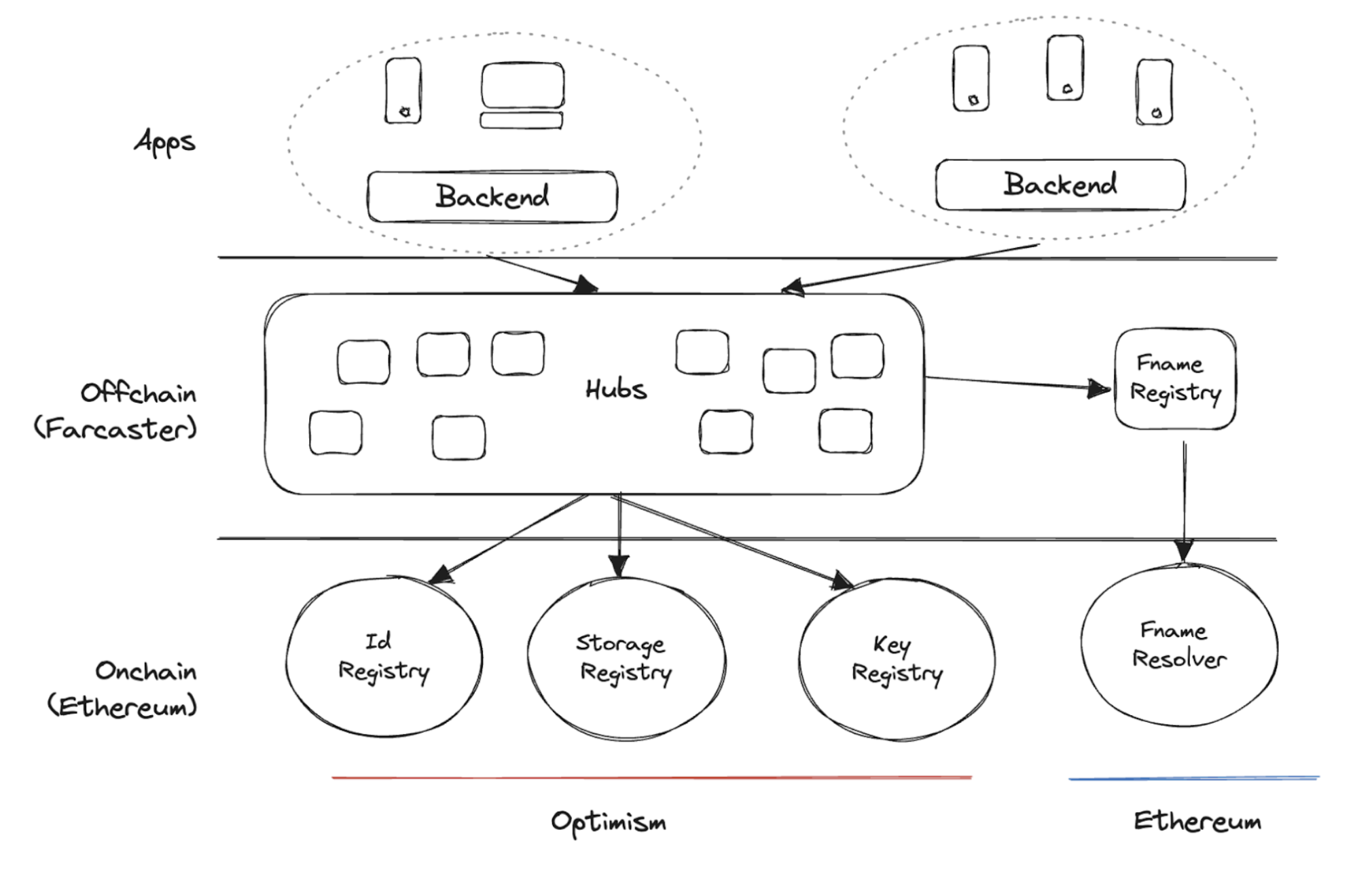

Farcaster is a decentralized social protocol built on Optimism, an Ethereum Layer 2 network.

- User Sovereignty & Privacy: At the data layer, Farcaster stores user social data (called "Casts") in an off-chain network of nodes known as "Hubs." In theory, users can run their own Hub to maintain control over and back up their data. Identity, on the other hand, is registered as an NFT on Optimism and controlled by the user's crypto wallet, similar to how ENS (Ethereum Name Service) works. Specifically, users need to get a username, rent storage space, and add a key to get started. However, front-end applications (like Warpcast) often abstract this process away for a smoother user experience, though the core principle of user control over their identity is preserved.

- Content Freedom & Algorithmic Transparency: The core protocol stays neutral. It doesn’t rank, filter or moderate content; every third-party client is free to use its own curation algorithm. That opens the door to competition—and real choice—for feeds.

- Open Source & Composability: Because Hubs are distributed and open-source, Farcaster is composable by default. The team also ships a Mini App SDK to make life easier for app builders.

From a technical tooling perspective, Farcaster primarily uses dWeb related technologies at its core. For instance, the crucial Hubs infrastructure utilizes CRDTs (Conflict-free Replicated Data Types) to handle data conflicts, and communication between nodes employs the Gossip Protocol (based on libp2p). The blockchain is mainly used for low-frequency, high-security scenarios like identity registration. (Note: Users can also opt to pay rent to store some data on-chain.)

|

|---|

| The architecture of Farcaster. Image source: Farcaster Docs |

Lens Protocol (v3)

Lens Protocol is also a decentralized social protocol built on the blockchain (Ethereum Layer 2). Users can interact with it through front-ends like hey or orb. The latest v3 version introduced a custom Lens Chain (ZKsync-style), specifically optimized for social scenarios.

- User Sovereignty & Privacy: Lens Protocol uses Smart Contract Accounts to represent identity and manages the user relationship graph via a "Graph" contract. Content storage is handled through a service layer interface called "Grove," which saves data on the decentralized storage platform IPFS (InterPlanetary File System).

- Content Freedom & Algorithmic Transparency: Lens introduces on-chain "Feed" smart contracts for content curation. Each Feed can be independently customized and deployed, and users can simultaneously use community-specific or global public Feeds, thereby achieving transparency and diversity in content rules.

- Open Source & Composability: Every social primitive — Account, Username, Graph, Feed, Group — is its own smart contract. Developers can mix and match them with on-chain Rules and Actions to build entirely new social behaviours. The whole design is deeply modular to spark innovation across the ecosystem.

From a technical tooling perspective, most interactions are expressed directly in smart contracts; only storage is off-loaded to deStorage services.

Nostr (Notes and Other Stuff Transmitted by Relays)

Nostr is a minimalist open protocol that uses Relays (WebSocket-based server) for message transmission and storage. Once you've set up a Nostr account, you can access it through any client built on the Nostr protocol, such as Iris, Damus, or Plebstr.

- User Sovereignty & Privacy: In Nostr, identity is represented by a public-private key pair from asymmetric cryptography. Users have full control over their private keys and don't need to undergo the KYC verification. Data is signed with the private key and sent to user-specified Relays. This private key signature addresses issues of tampering and authenticity—for instance, notes with invalid signatures are often discarded by Relays. This ensures message immutability but also leads to data fragmentation and complicates management.

- Content Freedom & Algorithmic Transparency: Since Relays are limited to simple storage and forwarding, Nostr itself doesn't offer any content algorithms. All content display and ranking are entirely up to third-party clients. Furthermore, users can freely choose their Relays, giving the system a naturally high degree of content freedom and censorship resistance. However, precisely because data is stored disparately across different Relays, clients wanting a global view of data need to aggregate it themselves.

- Composability & Emergent Innovation: Nostr's design is extremely minimalist, with open-source specifications, relying on just a few NIPs (Nostr Implementation Possibilities) as its core. This ultra-simple architecture leaves vast room for application composability and innovation.

Technically speaking, I see its essence as similar to dWeb's pubsub. Since there's currently no economic incentive to maintain Relays, its sustainability is a concern. However, we've seen many similar cases, so it's quite possible that someone will build on top of this protocol, add some economic incentives, and create something like a global bulletin board.

Mastodon

Mastodon is a federated microblogging platform based on the ActivityPub protocol and also a core component of the Fediverse. Conceptually, the Fediverse is an ecosystem, ActivityPub is its common language, and Mastodon is an application within this ecosystem. Users can choose to join existing instances or set up and run their own (I don't have a CS PhD, so I use Node / Instance / Server interchangeably at whim). They have full control over their data and content publishing rights on their instance, and each instance can set its own community guidelines.

- User Sovereignty & Privacy: Users register on a specific instance, and their data is stored on that instance's server. Identity is tied to the instance (e.g., @user@instance.social). Users can use export/import functions to migrate their accounts to other instances, but: (a) compatibility between two instances is ensured by a "soft" Server Covenant, somewhat like Ethereum's concept of social consensus; and (b) historical posts from the old instance are not transferred, so to see previous posts, you have to go back to the old instance, which makes for a very fragmented experience. Privacy depends on the instance administrator, who can define specific publishing settings for users.

- Content Freedom & Algorithmic Transparency: Algorithms and the degree of content freedom are defined by each instance administrator. The spirit of the Fediverse is to offer enough diversity for users to find their own "Cozy Web."

- Composability & Emergent Innovation: Mastodon itself is open-source. The ActivityPub protocol is also an open standard, allowing Mastodon to interoperate with other applications in the Fediverse.

Bluesky

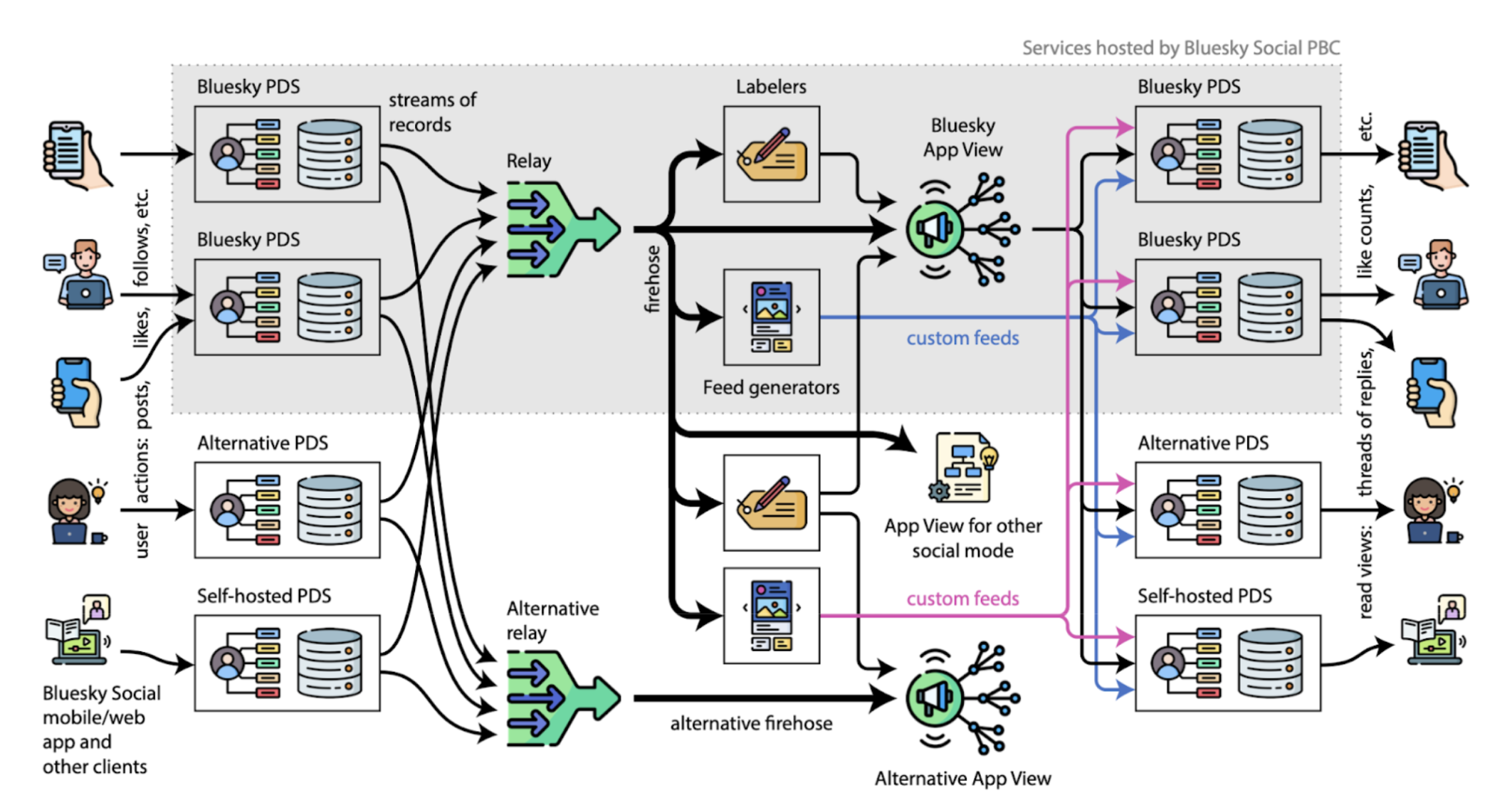

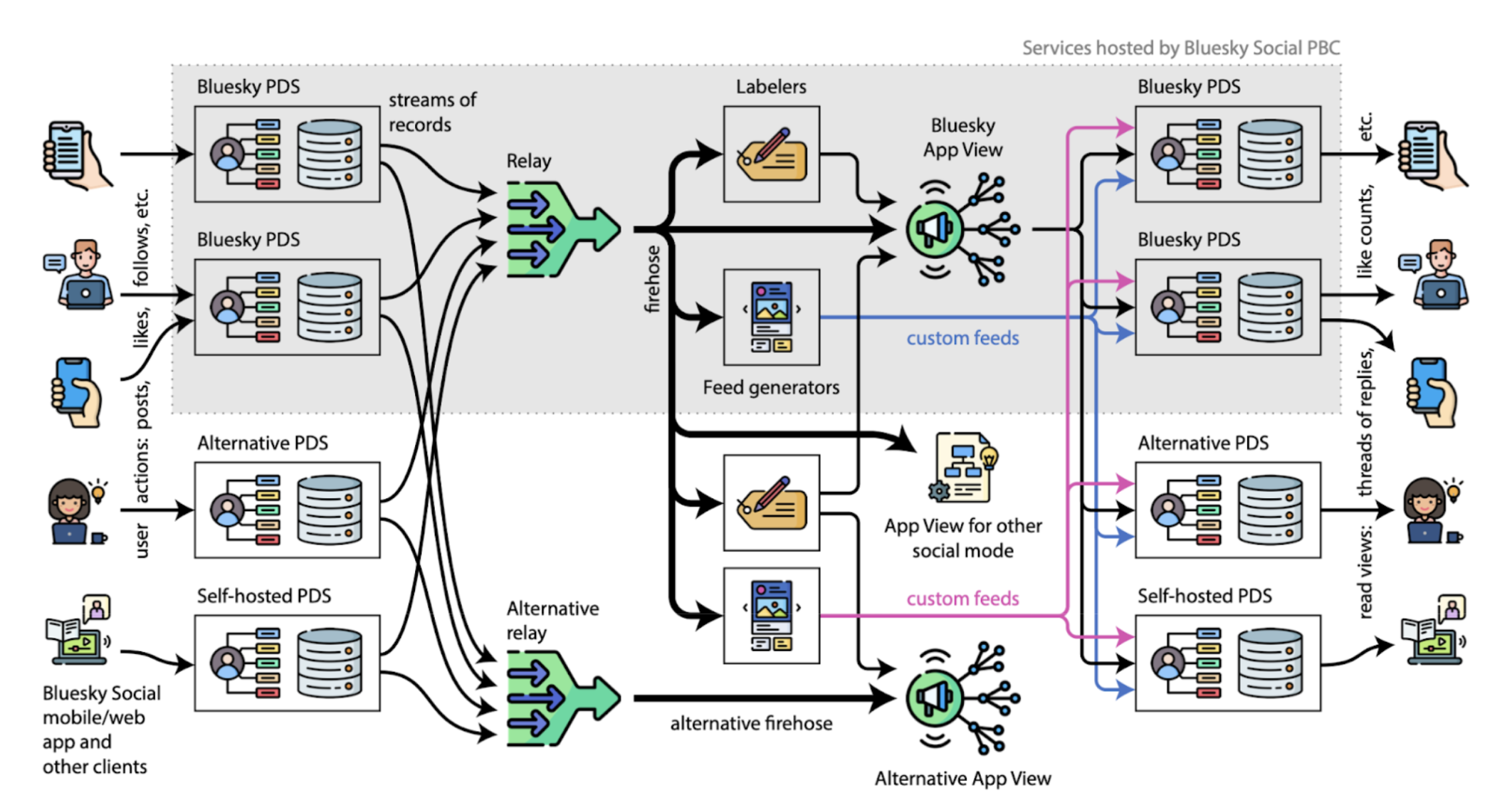

Bluesky, championed by a former Twitter CEO, offers a concrete decentralized social solution called the AT Protocol (Authenticated Transfer Protocol).

- User Sovereignty & Privacy: User data is stored on PDSs (Personal Data Servers). Users can choose to use Bluesky's official PDS, a third-party one, or set up their own, and can freely migrate their data. For identity, Bluesky adopts a mainstream SSI approach, using W3C specifications. In addition to supporting

did:web, it also introduces a new identifier,did:plc(where PLC stands for Public Ledger of Credentials), to achieve features like strong consistency, recoverability, and cheap cryptographic broadcasts. - Content Freedom & Algorithmic Transparency: Users ultimately receive data after it goes through the following pipeline: first, a Relay aggregates data from all PDSs. This data is then sent to Ozone (a labeling system) and Feed Generator. After being labeled, moderated, and sorted by content algorithms, it's finally consolidated in the App View, which is what the user sees. Users can customize their Feed Generator to choose their content algorithms, customize Ozone to decide on labeling, and customize the App View to determine the final presentation.

- Composability & Emergent Innovation: Besides the officially maintained versions, Feed Generators, Ozone, and App Views can all be customized. Furthermore, Ozone and Feed Generators are highly composable. For example, users can subscribe to others' labels or incorporate algorithms set up by others into their own data pool.

Bluesky calls this entire bundled architecture the AT Protocol. It allows users to control their data and identity through a federation structure, enhancing privacy protection. This means users can run their own PDS instances to host their own user information. Looking at its tech stack, Bluesky doesn't use blockchain or programmable cryptography tools. Instead, it draws more inspiration from dWeb. For a more detailed introduction, you can refer to this article or the official documentation.

|

|---|

| The architecture of Bluesky. Image source: Bluesky and the AT Protocol |

Based on the observations above, we can identify several things:

- Despite claims of improved efficiency, programmable cryptography has not yet seen widespread adoption in high-frequency, low-security scenarios like socials.

- When it comes to security and privacy, the solution still revolves around asymmetric cryptography or the removal of centralized servers.

- dWeb remains the primary arsenal of tech stack. On the blockchain front, cost considerations mean it's either avoided entirely or used for low-frequency, high-security needs like identity. If really wanna use it, one would need to build a custom chain, much like Lens has done.

- While decentralization offers some advantages, its drawbacks in terms of fragmentation are also readily apparent.

- The so-called "composability" is significantly limited because each solution has its own tech stack. For instance, among the five protocols/platforms mentioned, tools like Bridgy, Mostr, and Ditto have been developed to bridge them, and content aggregators like RSS3, Openvibe, and Yup also exist. However, by and large, this interoperability isn't native. Besides the extremely high switching costs, information like post likes cannot be transferred across platforms.

Note: Today's centralized social media companies also make extensive use of distributed system designs. However, their main goal is to meet Service Level Agreement (SLA) requirements—to prevent single points of failure, handle massive spikes in traffic, and optimize large-scale computation and storage resources. Therefore, we cannot simply equate decentralization with using distributed systems.

Can These Technologies Truly Slay the Dragon?

Ultimately, technology exists to serve humanity. This brings us to a more profound question: Can these designs and idealized technological combinations truly solve the various problems created by centralized platforms?

Better Content Curation: The Algorithm Problem

According to Metcalfe’s law, the value of a network is proportional to the square of the number of its users, regardless of what that "value" specifically is. Platforms always aim to increase their user count to maximize the network's overall value. As the user base expands, the volume of content inevitably explodes, leading platforms to naturally turn to algorithms to manage this information overload.

However, the original, simple purpose of content algorithms—to tag, rank, and filter content so users can find what interests them in an ocean of information and maintain a high signal-to-noise ratio—has often been compromised in practice for commercial reasons, usually at the expense of user attention. It's debatable whether this is a conflict between the user's Id and Superego, but it's a common criticism.

The solution might be relatively intuitive to me: create a competitive ecosystem for algorithms, allowing users to freely choose their preferred method of content curation. We could design algorithms like an "extension store," where various options are available for users to pick and choose. A more advanced vision would be to establish a public, open "Algorithm as a Service" platform. Using a shared public information pool as the raw input, this would hand the final content decision-making power back to the client-side.

Content consumers want the best content, so we would want this public information pool to be sufficiently "public," without a long list of qualifiers in front of "the best." But defining what is "best" from a top-down perspective is nearly impossible; trying to measure the preferences of thousands of communities and users with a single, universal set of standards is one of the classic mistakes of technological utopianism. As the saying goes, "there's no accounting for taste," and one man's meat is another man's poison. When "the best" is impossible to define universally, perhaps the only viable strategy is to pursue "abundance"—allowing a diverse range of curation mechanisms to coexist, so that everyone can find the version they want in this pluralistic market.

Portability of Data and Identity

The concept of user data portability is relatively straightforward: users should be able to easily export their accumulated data from a platform in various formats. If the data needs to be tamper-proof and verifiable, deStorage services (like IPFS) or blockchain technology can get the job done. However, reliable, long-term storage comes at a cost. You either have to pay for it, rely on temporary platform subsidies, or become the product yourself. You can't have your cake and eat it too.

Identity portability, on the other hand, is far more complex and nuanced. When we talk about portable identity, we're not just chasing after a simple username and password or a private key (think of all those wallets addresses that are nothing but private keys). Nor are we just talking about follower-following relationships (think of all the contacts in your phone you haven't spoken to in years and likely never will again). What truly holds value is the reputation, persona, and social status embedded within that identity.

However, this reputation and social status are hard to quantify and even harder to export digitally. They often only make sense within a specific social context. The most basic attempts, like exporting a social graph, merely provide a static snapshot of relationships. Until your peers migrate to the new platform with you, this exported graph is like an empty credential.

Another approach is to bridge this social status to the real world. There's a sort of potential energy gap between the online and offline worlds. Those with high status in the real world can easily project their influence online—think of how Taylor Swift or Cristiano Ronaldo can gain a massive following on any social platform on the earth. In contrast, it's difficult for online influence to cross over into the real world; just look at all the influencers struggling to monetize their traffic. (Of course, there are exceptions like Mr. Beast or Casey Neistat, whose influence has broken beyond the confines of the internet).

Yet another attempt has been to create a reputation aggregator for the entire online world, trying to break down the barriers between dimensions. An early pioneer in this field was Klout, while a current example using on-chain data is OpenRank. Klout aggregated data from every social platform it could find, threw it all into an algorithmic pot, and cooked up a single number meant to represent "influence." This practice drew heavy criticism, as it seemed to encourage a bunch of narcissists to flood the digital world with junk, turning all our online interactions into something out of The Truman Show. As the screenwriter for The Truman Show said, "When you know there is a camera, there is no reality." OpenRank's approach is considerably more refined, with more applications for sybil resistance and custom algorithms. If you're interested, I recommend reading their documentation.

Perhaps, just like in the real world, the online world doesn't need a single, unified, quantitative social score. Likes and reputation can be judged as good or bad, but there's no need for a consensus, and certainly no need for it to be expressed through one universal quantitative system.

Privacy, Anonymity, and Proof of Personhood

Privacy and social often seem like a naturally conflicting pair. When we use a social network, we often implicitly accept a kind of "social contract": to have meaningful interactions with others, we must be willing to give up some personal privacy and adhere to certain norms and etiquette. In fact, isn't the reason we call some people friends because we shared a certain level of our secrets with them (or, if your sociology background prefers to call it "intersubjective reality")?

Anonymity is one method of protecting privacy. People have tried to build anonymous social networks in the past, and from the failed attempts of Whisper and Secret (setting aside their own operational blunders), we can learn a few things. First, anonymous environments are breeding grounds for malicious behavior. Second, the compliance and regulatory risks of anonymous social platforms are incredibly difficult to manage. And third, more fundamentally, anonymity makes it hard for users to gain any real social capital from their interactions, which undermines the very foundation of the social game itself.

The malice part is easy to understand. Having no "skin in the game" drastically reduces the credibility and value of what is said. Among a few friends sharing an intersubjective reality, we'd just call that person "talktalker (説説仔)."

The compliance issue highlights how outdated our current laws are. They can't catch the people who use tools for malicious ends, so they go after the people who make the tools. You know how it is—even if it's pointless, someone will always use that pointlessness to prove they're doing something. For example, the French government's recent attempt to detain Telegram founder Pavel Durov and the US government's arrest of Tornado Cash founder Roman Semenov reflect this awkward legal reality.

The value of social networks is a concept Eugene Wei discussed in his essay "Status as a Service." He describes how users participate in social networks as if they are playing a game, working to mine social capital from the platform. For example, on Twitter, it's about showcasing wit in 140 characters; on Instagram, it's about photography skills; and on YouTube, it's about editing and storytelling abilities. If these efforts lose their traceability to an identity, they can't be converted into meaningful social status. Anonymity, therefore, severely weakens this core game mechanic. (I highly recommend reading the original essay; it's full of brilliant insights.)

Of course, the recent rise of "Proof of Personhood" is an attempt to strike a balance between anonymity and identity verification. This mechanism was initially used mostly in fund distribution scenarios to prove that a user is a real person, not an AI or a bot. In theory, however, Proof of Personhood can be combined with anonymity to further protect user privacy while preventing large-scale thought manipulation and Sybil attacks from (AI) bot armies and content farms. Balaji Srinivasan's concept of "The Pseudonymous Economy" is an extension of this effort. He proposed to use cryptocurrency and blockchain technology to provide a channel for converting social capital for pseudonymous identities, thereby easing the pressure of forcibly linking our real-world and online identities. (I'm not sure how many of you, like me, have started to lurk indefinitely on Facebook precisely because it's now populated by friends from your foolish youth to your mediocre adulthood, with a large variance of familiarity?)

Returning to the essence of privacy, the right to privacy isn't just about personal data not being breached. More importantly, it's about having active control over your own information, including the ability to decide when, how, and to what extent you share your information with others or systems. This holds true whether you are pursuing freedom as non-domination, freedom as self-mastery, or freedom as non-interference. (For the differences between these three, you can refer to this introduction written by my good friend mashbean.)

Therefore, I believe that a decentralized social platform—one that is highly censorship-resistant, offers strong privacy protection, and maintains a high degree of freedom—should be considered essential public internet infrastructure for the 21st century. I foresee that the maturation of programmable cryptography will bring about a paradigm-shifting contribution in this area. I don't know if you can feel the excitement, but it's the excitement of being able to witness history in the making. :)

Smaller-Scale Social and the Federated Model

Dunbar's number is a concept from anthropology that, in a highly unscientific, imprecise, and illogical way, describes the correlation between the volume of the Neocortex and the number of meaningful, stable relationships one can maintain. The reason it's so popular is that, on some level, it intuitively matches our daily life experiences.

We can probably all recognize from our own experiences that truly meaningful, high-quality interactions tend to happen within small, intimate groups. I have friends who rarely post anything publicly online but share incredibly interesting, witty, and novel insights in one-on-one chats or small group conversations—the quality is so good it almost makes me feel guilty. This phenomenon is no accident: people typically only feel comfortable enough to be their complete selves in a relatively secure environment. These bottom-up, small-scale, diverse, and grassroot groups, or what the research collective Other Internet calls "Squads," are increasingly becoming a vital source for high-quality information.

One way to put this into practice is to impose clear limits on group size. However, judging from the experience of the former social platform Path, simply forcing a friend limit at the application layer doesn't work well. Such a design not only restricts a user's ability and efficiency in accumulating social capital but also sacrifices the benefits of scale.

A more promising direction is the so-called "federated model," or what could be called a tribalism-based social platform, like the previously mentioned Mastodon or Bluesky. Personally, I'm more inclined to support this model conceptually.

In the humanities, James C. Scott's Seeing Like a State tells us that when modern governments try to control and regulate the lives of their subjects through quantification or digitization, they often just create a false sense of order on top of a highly complex and diverse reality. In the sciences, Complexity Theory tells us that complex network topologies will inevitably give rise to new dimensions of complexity and corresponding emergent properties. We cannot summarize the whole without losing the details.

However, while the federated model is philosophically appealing, its implementation requires extremely careful design. As "Federation is the Worst of all Worlds" warns:

The threat model and economics of federated systems devolve to concentrating trust in the hands of a few, while missing out on the scale advantages of purely centralized solutions.

Unfortunately, Mastodon seems to have fallen into this exact trap. Luckily, Bluesky appears to have thought this through more deeply. By decoupling user identity and data from server/nodes and fetching information by directly subscribing to accounts, while also introducing a relay that can aggregate messages across multiple sources, Bluesky effectively strikes a balance between the advantages of scale and the autonomy of a federated model. This, in turn, allows for a true "Global Conversation" to form across different communities and nodes within the platform.

Closing: Are we simply the status-seeking monkeys?

It will not be easy, 100 years of failure cannot be undone in one day, but one day begins and today is that day. – Javier Milei

The history of social networking platforms is remarkably short; their rise has only been in the last decade or so. While I don't trust the taste of the masses most of the time, I remain optimistic about humanity's miraculous ability to adapt quickly and believe that the many mistakes made in the brief history of social media can be undone.

As the book Power and Progress predicts, technology and algorithms are seizing more political power. For instance, as mentioned in Careless People, Donald Trump's 2016 campaign team used Facebook's platform to achieve highly efficient voter conversion at an extremely low cost. When Mark Zuckerberg learned of this, his first reaction was reportedly, "I could run for president, too." You don't have to start as a dragon slayer to become the next dragon that needs slaying.

Despite all this, I stubbornly believe that a decentralized, distributed, privacy-preserving, censorship-resistant, and free social platform should be considered essential public infrastructure for the 21st century. However, figuring out how to combine this with humanity's status-seeking monkey nature, practicality, and need for entertainment to design the next generation of social products is a question I will continue to follow and explore.

屠龍少年與他的屠龍刀:凝視社交網路的深淵

「現實只不過是種幻覺,只是是種頑固的幻覺。」 —— 阿爾伯特 ·愛因斯坦

我高中的時候跟多數高中生一樣,課業、運動、戀愛幾乎佔據了我所有的時間。對於班上、補習班、學校、友校發生的事情,我有種明顯的遲鈍:彷彿那些資訊與我彼此敬而遠之,相看兩不厭,卻也從未真正交會。直到高二暑假,在某個營隊即將結束時,小組成員們交換聯絡方式,才讓我知道有個東西叫做臉書,這東西竟然不用付簡訊費就能傳訊息聊天,還能上傳照片與文字,看見彼此生活的近況。我至今還記得第一次進入這個新世界時的興奮:在一台宏碁藍色的筆記型電腦上,登入臉書,我看到了一張標注我名字的營隊大合照,除了會出現在自己的版面上之外,還能留言、點讚、分享。小組的夥伴建立了一個群聊的對話群組,大家熱絡的打招呼,分享參與感想與生活,期待未來還能再相逢等。現實的營隊似乎得以延續。(當然,這種熱絡隨著時間,以指數級速度降溫,小時候的世界總是有新的東西等著我們去探索,留戀與懷舊似乎是不存在的)

人類歷史上不乏這種充滿戲劇性的瞬間:某年某月的某一天,表面看來與其他日子毫無區別,但一個不起眼的念頭或決定,卻能以不可逆轉的方式改變了接下來無數代的人。在 2008 年,年輕的馬克・扎克伯格(Mark Zuckerberg)可能也沒有意識到,自己一時興起的實驗性平台,竟會深邃地重塑整個人類社會。無論喜歡與否,像 Facebook、Instagram、Reddit、Twitter、Tiktok 這樣的社交網路平台,在一個相對極短的時間內,改變的人與人之間溝通、互動、組織乃至合作的模式與效率。

對於後來出生、原生於網路世界的世代來說,這種改變或許不易察覺,但對於像我們這種經歷網路使用習慣轉換、夾處於兩個世代之間的人來說,這種巨變卻是清晰而深刻的。我們不僅親眼見證了一個新物種的誕生,也同時發現,這一進步背後猶如打開了潘朵拉的盒子,在資本的推波助瀾下,延伸了數不盡的問題。

明顯的有 / 一級效應(first order effect):

- 注意力經濟與沉迷: 當社交平台主要以廣告作為營利模式(廣告收入常常占九成以上),決定廣告價值的變數便集中在用戶的注意力品質、受眾消費力,以及市場供需。而其中最重要的「注意力品質」,本質上即為用戶對內容的沉迷程度。於是,各種平台的演算法被設計為「最大化用戶沉迷程度」的目標函數(objective function),產生了今日令人熟悉的數位上癮現象。

- 假訊息與錯誤資訊: 延伸自扭曲的廣告商業模式,由於危言聳聽的內容總能更有效地吸引用戶注意力,這些內容往往被平台演算法進一步放大。此外,造謠一張嘴,闢謠跑斷腿,內生的不對稱給了造謠者一個完美的環境傳播假訊息的環境,再加上現代社會盛行一種對真實性抱持虛無主義的態度,使這種問題更為棘手。

- 網路霸凌與仇恨言論: 在日劇中很常出現這種人物設定:一個男生,他在職場上,對於上司、客戶唯唯諾諾,顯得極為懦弱;但在家庭中,則會對妻子指手畫腳,一副霸道總裁的樣子。這種由於環境帶來的性格割裂性並不少見,雖說網路世界不是非法之地,但由於一定程度的匿名性,讓「酸民」、「站著說話不腰疼」的文化盛行,每個人都像是刻板印象中的計程車司機:國中畢業的學歷,卻過人的自信,上至天文下至地理皆有一套理論,總感覺自己的財政政策可以比央行總裁更有效。更別說這種過度自信的人群,打著正義的旗號,並在注意力演算法的助攻下,三位一體可以有的破壞力。

- 個資與隱私外洩: 當個資被視為一種有價值的資產時,擁有大量使用者資料的資料庫就如一個眾所皆知的顯眼金礦,自然也會有蜂擁而至的淘金者(aka 資訊世界的小偷)。更為嚴重的是,個人資訊的外洩具有兩種無法迴避的不對稱性:(a)洩漏的資訊具有單向性,難以彌補;(b) 整個系統的安全性取決於最脆弱的環節,即使絕大多數環節遵守了最佳實踐,只要有一個資安意識或能力不足的環節(例如政府機關或電信公司),則隱私安全性還是堪憂。

- 可以離開的權利: 當用戶對某個平台厭倦,無論出於政策、演算法或設計因素,實際上卻很難真正離開,因為放棄平台即意味著放棄累積的內容與社交圖譜(Social Graph)。

相對不明顯的有 / 二級效應(second order effect):

- 演算法導致的同溫層與極化: 內容演算法的核心是注意力,注意力的核心是將「討喜的資訊流」匹配給相對應的用戶。舒適圈其定義本身就是讓人感到舒適,無論用戶嘴上怎麼說,多數人是不願意長期跳脫出舒適圈的,而不可避免的,容易產生同溫層(echo chamber)與極化。是好是壞是個值得討論的話題,近期常被提到的「多元宇宙主義」(Plurality)、「部落主義」(Tribalism)與「小隊文化」(Squads Culture),或許正是對這種現象的一種文藝復興式回應。

- 選舉與民主韌性受損: 更嚴重的是,民主制度的韌性亦因社交媒體而受損。當假資訊泛濫並導致真實性陷入無盡的追尋與質疑時,人們便容易陷入一種犬儒主義與虛無狀態。真相變得無足輕重,人與人之間再無法達成共識,看看《千萬別抬頭(Don't Look Up)》便知。這正是獨裁者們夢寐以求的局面:當真善美都失去了共同的評判基礎,假惡醜也將不再存在。

為什麼人們又開始討論「去中心化社交」?

社交網絡自興起以來,一直是創業者的熱門領域(也為臉書提供源源不斷的抄襲素材 lol)。早在 2010 年代初,已有不少嘗試透過不同的技術與設計,解決中心化社交平台帶來的問題。例如:

- App.net:一個類似 Twitter(抱歉了,它對我來說永遠叫做 Twitter)的變體,其初衷是移除廣告元素、不販賣使用者數據,並透過開放 API,允許開發者自由地擴展平台功能。不過,儘管用戶渴望更多隱私與自主權,卻鮮少有人真正願意為此付費,導致其難以持續。

- Diaspora:一個由用戶自行運行節點(稱為 Pods)的社交網絡,承諾用戶完全掌控自身數據與隱私,強調無單點故障、允許匿名及假名、同時奉行社群自治與開源精神。

- Path:一個最初將朋友數量限制在 50 位的平台,試圖透過更緊密的社交圈,建立更深入、更有意義的人際連結。

- Peach:一個特意排除演算法推送與標籤(hashtag)的平台,試圖讓用戶擺脫「注意力爭奪」的困境,專注於純粹的人際互動。

重溫這些過去的嘗試並非本文重點,但它們確實提供了一個重要的歷史脈絡,告訴我們:現今許多關於社交網絡的困境,其實並非新鮮問題,且長期以來總有人嘗試提出解答。歷史不會重複,但往往押韻。許多看似全新概念的想法早已在過去被提出,唯有當時代的技術條件尚未成熟,使這些構想無法真正落實,例如 19 世紀的「電腦」、1910 年代的「飛天汽車」,或 1950 年代首次被提出的「人工智能」。如今,隨著新技術逐漸成熟,許多曾被視為過於超前的想法再度被取出檢視與嘗試,而當下對「去中心化社交」的重新討論,也正是如此。屠龍的少年們,兩眼帶刀,充滿驕傲,領先同世代的看到了打造一把好屠龍刀的可能性。

打造次世代屠龍刀的新素材能簡單分為三類:

- 區塊鏈(Blockchain):一種較堅固的網路建設材料,有人拿來當儲存空間,有人拿來當時間戳記服務,有人把身份刻在上面。

- 可編程密碼學(Programmable Cryptography):一系列保護隱私的魔法,主要包含零知識證明(Zero-Knowledge Proof, ZK)、全同態加密(Fully Homomorphic Encryption, FHE)、不可區分混淆(Indistinguishability Obfuscation, iO)。

- 去中心化網路(dWeb):更古老的社群以及技術堆棧,包含點對點傳輸技術(Peer-to-Peer, p2p)、分布式系統(Distributed System)、以及去中心化存儲(dStorage)。

如何定義「去中心化社交」?

若試圖透過技術特徵直接定義去中心化社交,通常會遇到許多困惑。表面上,號稱去中心化的社交平台往往具有以下幾種特徵:

- 允許用戶透過加密貨幣錢包登入,省略傳統身份驗證(KYC)流程;

- 將用戶產生的內容上傳到某種分布式儲存空間,確保內容不易被單方面刪除;

- 將用戶間的互動關係,透過特定壓縮的方式(如雜湊)記錄於區塊鏈,確保互動關係的唯一性與可驗證性。

然而,這種「技術導向」的定義隨即會引發更多的問題,例如:

- 如果上傳的鏈是一條相對中心化的鏈(例如 BSC)還能算是去中心化嗎?

- 究竟是哪些資料上傳至分布式儲存空間?用戶是否能夠輕易地從這些儲存空間中重新獲取自身的資料?

- 如果平台關掉了,有這些互動關係的雜湊(hash)資料,用戶可以遷移到另外一個新的伺服器,而重現這些互動關係嗎?

從以上問題可知,單純以技術方案定義去中心化社交存在明顯的侷限性。去中心化這個詞本身即模糊且多義,而社交網路又存在身份認證、資料儲存、內容策展與社群管理等多重維度,因此僅從技術角度切入,難免會出現見樹不見林的窘境。事實上,技術終究只是工具,而非目的本身。

或許更妥善的方式是反向思考:先辨識出現有社交平台令人明顯感到困擾與厭惡的元素,再從這些負面元素反推,定義出我們真正渴望的理想品質。然後,才回頭檢視當下的技術能夠在何種程度上實現這些特質,以及實踐時所需付出的成本。

借用坐標軸轉換的概念,這就像是將技術的三維空間,轉換到最終用戶想要的特徵的三維空間:

- 個人數據與身份自主:用戶想要對帳號與資料有更高的控制權利,無論這句話具體是什麼意思。除了不想辛苦建立的帳號能隨時被單方面的關閉之外,通常還包括更細膩的隱私保護、資料可自由匯出與備份,以及身份與社交圖譜的可攜性。隱私保護通常涉及可編程密碼學,內容與數據往往牽涉好的 API 或是去中心化存儲(deStorage),身份與社交圖譜則可以與身分自主權(Self-sovereign Identity, SSI)、分散式身分(Decentralised Identity, DID)、數位身分皮夾(Digital Identity Wallet, DIW)相關。

- 內容自由與演算法透明:用戶期待更具透明性與可選擇性的內容策展,想脫離商業演算法的操控,進一步拿回注意力的主導權。內容審查、假新聞、AI 機器人生產的垃圾內容等都是巨大的問題,且往往存在某種拮抗,例如當完全無審查的平台,出現未成年色情、槍枝毒品販賣內容該怎麼合規。除了試圖建立某種開源透明,具可信中立性(Credible Neutrality)的演算法外,另一種務實且有價值的做法是提供多種演算法的選擇。區塊鏈有機會提供可信中立性,去中心化網路技術則有機會提供可自定義性。

- 可組合性與創新湧現:如果你看過「連結放在評論區」這種民間智慧,反映出我們現在的社交網路平台是個封閉的國度:獨裁者站在自私自利的角度,有意識的建構起了一個長城,讓資訊裡外不流通。撇除使用者的基本權利來說,這樣的閉鎖扼殺了湧現的可能性:即便只具有簡單的元素,但足夠的開放性,都能讓用戶們的創意完整發揮,讓一個世界更好玩。例如用戶在《薩爾達傳說》的中打造電子電路、雷擊米老鼠,或各種騷操作;在《我的世界》打造文明等等都是案例。技術上,以基於區塊鏈技術的超結構(Hyperstructures)作為底層材料,可以獲得天生良好的可組合性,自主世界(Autonomous Worlds)就是其中最前沿的嘗試。不需要無許可性(permissionless)的話,則秉持開放精神的 API 或將核心組件設定為開源協議(Open Source Protocol) ,皆足以提升可組合性與創新。

回到屠龍刀新素材的隱喻,正如合金是通過混合不同元素來創造出比單一金屬更優越性能的材料,在實務中,技術素材也往往會混搭使用以解決具體問題。例如 AnonCreds 結合了 DID 與 ZK 技術,Filecoin 將 dStorage、Blockchain 與 ZK 技術融合,Tornado Cash 則融合了 ZK 與 Blockchain 等。

最後,值得一提的是,社交金融化(SocialFi)在我看來更像是將區塊鏈金融功能疊加於傳統社交網絡之上,並未真正解決核心的去中心化問題。如馬克思所言,基礎設施決定上層建築,若底層未真正去中心化,表面上的金融層變化也難以帶來實質的社交轉型。例如某天臉書把貼文都鑄造成 NFT,允許用戶用穩定幣互相打賞,主要在上述三個維度上沒有改善,在我看來還是一個偏向中心化的產品。

現有產品的嘗試

讓我們套用上面的框架,來感受一下目前市面上比較知名的幾個去中心化社交產品,理解它們各自選擇了哪些路徑,以及在具體實踐中如何回應上述的問題。

Farcaster

Farcaster 是基於以太坊第二層網路 Optimism 構建的去中心化社交協議。

- 個人數據與身份自主:在數據層面,Farcaster 將用戶的社交數據(稱為 Casts)儲存在稱為「Hubs」的鏈下(off-chain)節點網絡之中,用戶理論上可自行運行 Hub,以掌控與備份自己的數據。身份則以 NFT 的形式登記在 Optimism 上,由用戶加密錢包控制,這與 ENS 的邏輯類似。具體來說,會需要獲取一個用戶名、租用存儲空間並添加一個密鑰才能開始使用,但實際使用時,多由前端應用(如 Warpcast)抽象化此流程,但其本質仍保留了用戶對身份的主控權。

- 內容自由與演算法透明:協議本身保持中立,不介入內容的具體呈現與排序,內容的篩選、展示完全由第三方客戶端自行決定。這允許了多樣化的內容策展演算法得以自由競爭與共存。

- 可組合性與創新湧現:由於 Hub 的設計是分布式且開源的,所以天生的可組合性不錯。此外,Farcaster 團隊寫好 Mini App SDK 來對應用層的開發者釋出善意。

技術工具方面來看,farcaster 用 dWeb 相關技術作為核心,例如最關鍵的 Hubs 方面的搭建用了 CRDTs 來處理資料衝突問題,節點之間的溝通用了 Gossip Protocol (基於 libp2p ),區塊鏈僅用於身份註冊等低頻、高安全性的場景。(註:用戶也可以選擇付租金把一些資料上鏈)

|

|---|

| Farcaster 架構圖,來源:Farcaster Docs |

Lens Protocol (v3)

Lens Protocol 同樣是一個基於區塊鏈(Ethereum Layer2)的去中心化社交協議,使用者可以搭配 hey 或 orb 等前端來互動。最新的 v3 版本推出了特製的 Lens Chain( ZKsync 風格),專為社交場景而優化。

- 個人數據與身份自主:Lens Protocol 以智能合約帳戶(Smart Contract Account)作為身份代表,並透過「Graph」合約管理用戶間的關係圖譜。內容儲存則通過稱為「Grove」的服務層介面,將資料保存於去中心化儲存平台 IPFS 上。

- 內容自由與演算法透明:Lens 引入鏈上「Feed」智能合約來進行內容策展,每一條 Feed 都可獨立定製部署,並可同時使用社群專屬或全局公共 Feed,從而實現內容規則的透明與多樣。

- 可組合性與創新湧現:Lens Protocol 的每個社交原語(Social Primitive)都是獨立運作的智能合約,包括「帳戶 (Account)、使用者名稱 (Username)、關係圖譜 (Graph)、資訊流 (Feed) 和群組 (Group)」等,並允許開發者透過鏈上「規則」(Rules)與「動作」(Actions)自由定製並組合各種社交功能與行為模式。其整體設計理念即以高度模組化來促進生態內的湧現性與創新。

技術工具方面來看,絕大多數用的是區塊鏈的工具,主要互動皆以智能合約表達,只在儲存方面用了去中心化儲存的配套服務。

Nostr (Notes and Other Stuff Transmitted by Relays)

Nostr 是一個極簡的開放協議,透過 Relays(基於 WebSocket 的中繼器)實現訊息傳輸與存儲。創建了 Nostr 帳戶後,可以通過任何基於 Nostr 協議的客戶端(像是 Iris、Damus 或 Plebstr)來訪問它。

- 個人數據與身份自主:Nostr 的身份是透過非對稱加密的公私鑰表示,用戶完全掌控私鑰,無須進行任何 KYC(身份驗證)。數據則以私鑰簽名的方式傳送至用戶指定的中繼器們,私鑰簽名可以用來解決篡改與真實性的問題,例如無效簽名的筆記往往會被 Relay 丟棄。這確保了訊息的不可篡改性,但也造成數據的碎片化與管理的複雜性。

- 內容自由與演算法透明:由於 Relay 的角色僅限於簡單存儲與轉發,Nostr 自身不提供任何內容演算法,所有內容展示與排序完全取決於第三方客戶端。此外,用戶可自由選擇 Relay,使其天然具備極高的內容自由度與防河蟹能力。然而,也正因為資料是割裂的儲存在不同的 Relay 上,想要看到全局資料的客戶端需要自行去聚合。

- 可組合性與創新湧現:Nostr 的設計極度簡約、規範開源,僅以少量的 NIP 規格(Nostr Implementation Possibilities)作為核心,這種極簡架構為應用的可組合性與創新預留了巨大空間。

技術上在我看來,其本質與 dWeb 的 pubsub 是雷同的。由於目前維護 Relay 是沒有經濟上的誘因的,目前的可持續性堪憂。不過我們也看過許多類似的案例,所以有人在這個協議之上,加入一些經濟誘因,弄一個全局的佈告欄是很有可能發展的事。

Mastodon

Mastodon 是基於 ActivityPub 協定的聯邦式微部落格平台(Microblog),同時也是 Fediverse (聯邦宇宙) 的核心組成部分。關係層面上,Fediverse 是一個生態系,ActivityPub 是這個生態系的通用語言,而 Mastodon 是這個生態系中的一個應用。用戶可以選擇加入或自行架設節點運行實例( instance,抱歉,我沒有 CS PhD,我總是將 Node / Instance / Server 隨心所欲的交替使用),能完全掌握其數據和內容發布權限,各實例可設定自有的社區準則。

- 個人數據與身份自主:用戶在特定的實例上註冊,數據存儲在該節點的伺服器上。身份方面是與實例綁定的 (@user@instance.social)。用戶可以用匯出匯入功能來將帳戶帳戶遷移到其他實例上,但 (a) 兩個實例之間兼容性是靠軟性的伺服器公約(Server Covenant)來保障的,有點像是以太坊講的社群共識(Social Consensus) (b) 舊實例的歷史貼文是不會轉移的,所以想看之前的貼文,則需要到舊的實例,屬於非常割裂的體驗。隱私性方面則取決於實例管理員,可以規定用戶具體的發布設置。

- 內容自由與演算法透明:演算法與內容自由度由各個實例管理員來定義,聯邦宇宙的精神是有足夠的多樣性,讓用戶找到自己的舒適網(Cozy Web)。

- 可組合性與創新湧現:Mastodon 本身是開源的。ActivityPub 協議也是開放標準,讓 Mastodon 可以與 Fediverse 中的其他應用互相操作。

Bluesky

Bluesky 由前 Twitter 執行長推動,提供了一種具體的去中心化社交方案,名為 AT Protocol (Authenticated Transfer Protocol,認證傳輸協議)。

- 個人數據與身份自主:用戶數據存儲在 PDS (Personal Data Servers,個人數據伺服器) 中,用戶可以自由選擇用 Bluesky 官方的、 第三方提供的、或自己搭建的 PDS,並自由遷移數據。身份方面則使用了主流 SSI 的思路,使用了 W3C 的規範,除了支援 did: web 之外, 另外新定義了 did: plc (PLC 指的是 Public Ledger of Credentials) 來做到強一致性、可復原、加密廣播等特性。

- 內容自由與演算法透明:用戶獲得最終資料的方式是,先由 Relay 聚合所有 PDSs 的資料,送給 Ozone(標注與審核系統)與 Feed Generator ,在標記、審核、內容演算法排序之後,在 App View 來進行最終統整之後,就是用戶最終看到的頁面。用戶可以自定義 Feed Generator 來自決定內容演算法,自定義 Ozone 來決定如何標記,自定義 App View 來決定最終呈現。

- 可組合性與創新湧現:Feed Generator、Ozone、App View 除了官方維護的版本之外,皆可以自定義。另外,Ozone 與 Feed Generator 皆具有高度可組合性,例如可以訂閱他人的標註,組合他人設定的演算法進入自己的資料池中。

上述的整套架構打包在一起,Bluesky 將其稱為 AT Protocol。允許用戶透過 Federation 結構(意味著一組節點可以相互發送消息)控制其數據和身份,增強隱私保護。這意味著用戶能夠運行自己的 PDS 實例,承載他們自己的用戶信息。技術堆棧方面可以發現,Bluesky 沒使用區塊鏈與可編程密碼學的工具,更多的是從 dWeb 找靈感。更詳細的介紹可以參考這篇文章或是官方文檔。

|

|---|

| Bluesky 架構圖,來源:Bluesky and the AT Protocol |

綜合上述觀察,我們不難注意到一些值得深思的共同現象:

- 無論如何宣稱效率上的提升,目前可編程密碼學尚未廣泛應用於社交這種高頻次低安全需求的使用場景。

- 安全與隱私方面的表達,更多的還是用非對稱密碼學,或是移除中心化伺服器來達成。

- dWeb 還是最主要的工具軍火庫。區塊鏈方面由於成本考量,要麼直接不用,要麼用於低頻次高安全需求的身份。如果真的想用,就需要像 Lens 那樣自己打造客製化的鏈。

- 在擁有一些優點的同時,去中心化的在分割性方面的缺點也明顯可見。

- 由於各家解法都有各自的技術堆棧,讓所謂的可組合性也是有明顯局限的。例如上述在五個協議/平台之間,雖然有人開發橋接的工具,例如 Bridgy、Mostr、Ditto;或是內容的聚合器,例如,RSS3、Openvibe、Yup。但總的來說,都不是原生的互通可組合,除了有極高的遷移成本之外,貼文點讚等資訊都是無法跨平台的。

註:當下中心化社交網路公司,往往也都大量應用分布式系統的設計,但其主要目的是有服務等級協定(Service Level Agreement, SLA)要求,目的為避免單點故障、應付瞬時大流量、優化極大規模計算與存儲資源等。所以我們無法將去中心化,簡單的理解為單純的將中心化伺服器改為用戶自己維護伺服器。

靈魂拷問:有這些技術就能真的能屠龍嗎?

技術最終的目的是服務人性,因此我們更需要深入追問:透過這些看似完善的設計與理想化的技術組合,是否真的能解決中心化平台帶來的種種困境?

更好的內容策展:演算法的問題

根據梅特卡夫定律(Metcalfe’s law),網路的價值正比於用戶數的平方,無論這個價值究竟是什麼。平台總傾向於增加用戶數量,以最大化整體網絡價值。伴隨用戶規模的擴張,內容量也將無可避免地爆炸式增長,而平台自然會轉向演算法來處理這些過量的資訊。

然而,內容演算法最初單純的設計目的——即標註、排序、篩選內容,使用戶得以在資訊海洋中快速找到符合興趣的訊息,保持高「信噪比」。出於商業的考量,這理想在當今的實踐中,往往以奪取用戶注意力為代價。無法分辨這是不是用戶本我(Id)與超我(Superego)之間的不協調,但這是種常見的批評。

解決之道或許相對直覺:建立一種演算法的競爭生態,允許用戶自由選擇自己喜好的內容策展方式。我們或可將演算法設計成一種類似「插件商店」的機制,存在多種演算法可供使用者自由選配;更高層次的設想則是,建立一個公共、開放的「算法即服務」(Algorithm as a Service)平台,透過共用的公共資訊池為輸入原材料,將最終的內容決策權交給用戶端。

內容消費者追求的是最好的內容,所以我們會想要這個公共資訊池足夠的「公共」,不希望在「最佳」前面加入複數個限定詞。但何謂「最好」是難以自上而下的統一定義的,想要透過一套統一量化的標準衡量成千上萬的社群與用戶偏好,無疑是科技烏托邦主義者常犯的錯誤之一。眾口難調,人類的悲喜並不相通,當「最好」難以統一定義時,或許真正可行的策略是追求「豐饒」,允許足夠多樣的策展機制並存,讓每個人都能在這個多元的市場中找到自己想要的版本。

數據與身份的可攜帶

用戶數據的可攜性相對明確:用戶應該能夠輕鬆地從平台匯出自身累積的數據,並支援多樣化的匯出格式。如果數據需要具備一定的防篡改性與可驗證性,那麼去中心化儲存服務(如 IPFS)或區塊鏈技術便足以解決。然而,長久可靠的儲存是有成本的,要麼付錢租用,要麼平台暫時性的補貼,要麼把自己成為某種商品,無法既要又要還要。

至於身份的可攜帶,則更為複雜且微妙。我們所謂的身份可攜,所追求的並非單純的帳號密碼或私鑰(試想那些空有私鑰的錢包),亦非僅僅是用戶與其他用戶之間的追蹤與關注關係(想想那些躺在通訊錄中那些過去數年皆未聯絡,可預見的未來終將不再聯絡的聯絡人),真正有價值的,是這些身份背後所蘊含的聲譽、人設與社交地位。

然而,這些聲譽與社交地位難以量化,更難以直接透過程式匯出,往往必須依附於特定的社交脈絡才能有效呈現。最基礎的嘗試,如匯出社交圖譜,僅是提供一張人際關係的靜態快照,在同伴們尚未一同遷移到新的平台之前,這種匯出像是一張空洞的文憑。

另一種方式是將這種社交地位,橋接積累到真實世界中。網路世界與真實世界地位有種位能(Potential Energy)上的差異,真實世界高地位者,可以輕易的將現實影響力投射進網路世界,例如 Taylor Swift 或 Cristiano Ronaldo 可以在任意一個社交平台獲取巨大的追隨者;相對的,網路世界的影響力要進入真實世界是困難的,想想那些著急著無法將流量變現的網紅們。(當然,也有像 Mr. Beast 或 Casey Neistat 這樣影響力突破網路的特例)。

還有一種嘗試是做一個全網路世界的聲譽聚合器,試圖直接打破次元。早期嘗試的先烈是 Klout,當下使用鏈上資料的案例是 OpenRank。 Klout 聚合所有能找得到的社交平台資料作為食材,丟入一個算法鍋,然後烹飪出一個“代表影響力”的數字。這種做法引來許多批評,因為它似乎鼓勵一群自戀狂成天向數位世界製造垃圾,並讓我們所有的網上社交像是一個楚門的世界。正如《楚門的世界》編劇說的:「當你知道有攝影機時,就沒有現實。(When you know there is a camera, there is no reality.)」。OpenRank 的作法相對精細許多,並有更多的關於防女巫攻擊、客製化演算法的應用,有興趣的可以閱讀其文檔。

或許,與現實世界相同,網路世界也不需要一個統一的、量化的社交數值。喜愛與口碑或許可以有好壞之分,但無需達成共識,更無需透過統一的量化機制表現。

隱私、匿名、人類證明

隱私與社交似乎是一組天然相互牴觸的概念。當我們使用社交網絡平台時,往往意味著我們主動或被動地接受了一種「社會契約」:為了與他人進行有意義的互動,我們必須願意放棄一部分的個人隱私,遵循特定的規範與禮儀。事實上,我們之所以將一些人稱為朋友,不正是因為我們願意與之分享一定程度的秘密(或你的社會學素養讓你喜歡稱之為「互為主體的現實(intersubjective reality)」)嗎?

可匿名性是一種保護隱私的手段。曾有人曾經試圖打造匿名的社交網路,撇除自身糟糕的操作之外,從 Whisper 與 Secret 失敗的嘗試中我們可以學習到:第一,匿名環境極易滋長惡意;第二,匿名社交的合規與法規風險難以有效管理;第三,更為根本的是,匿名性使得用戶難以從社交互動中獲取真正有價值的社會資本,從而損害了社交遊戲本身的存在基礎。

惡意是容易理解的,沒有切膚之痛會大大降低言論的可信度與價值,在幾位共享互為主體的現實的朋友之間,我們稱之為「説説仔」。

合規問題顯示了當下法律的落後。他們抓不到使用工具作惡的人,只好去抓製造工具的人,你懂的,即便毫無意義,但總是有人會透過這種無意義來證明自己。例如,近年法國政府試圖拘捕 Telegram 的創始人 Pavel Durov,美國政府則拘捕了 Tornado Cash 的創始人 Roman Semenov,便反映了這種尷尬的法律現狀。

社交網路價值是 Eugene Wei 在《地位即服務 (Status as a Service)》 中提到的觀念,他描述用戶參與社交網路平台就是像參與一場遊戲,透過某種努力來挖取平台上的社會資本,例如 Twitter 是用 140 字來展現幽默,Instagram 是展現拍照技術,Youtube 是展示剪輯與說故事的能力。這些努力若失去身份的可追溯性,便難以轉換成有意義的社會地位,匿名性便因此而嚴重削弱了這種遊戲的核心機制。強烈推薦去看原文,當中有許多精彩的理解。

當然,近來興起的「人類證明(Proof of Personhood)」試圖為匿名性與實名之間尋找平衡。該機制最初多應用於資金分配場景,以證明用戶是真實個人,而非 AI 或機器人。但從理論上看,「人類證明」完全能與匿名性結合使用,進一步保護用戶隱私,同時防止網軍與內容農場的大規模思想操控與女巫攻擊。Balaji Srinivasan 提出的「假名經濟(The Pseudonymous Economy)」便是此種努力的延伸,他試圖透過加密貨幣與區塊鏈技術,為匿名或假名身份提供社會資本的轉化渠道,以減緩現實身份與網路身份強制綁定所帶來的壓力——不確定你們有多少人像我一樣,正因臉書上累積了從年少無知到年老平庸、熟悉程度標準差巨大的朋友,而選擇開始無限期潛水的?

回到隱私的本質,隱私權不僅指個人資料不被侵犯,更重要的是個人擁有對自身資訊的主動控制權,包括能夠自主決定何時、如何、以何種程度分享自身資訊給他人或系統。不論是追求不被支配的自由(Freedom as non-domination)、自我主宰的自由(Freedom as self-mastery)、亦或是免於干涉的自由(Freedom as non-interference)(三者的差異可以參考好朋友豆泥寫的介紹)。

因此,我認為具備強抗審查性、良好隱私保護、同時維持高度自由的去中心化社交平台,應被視為 21 世紀人類重要的網路公共基礎建設。我預見可編程密碼學的成熟,將可以在此方面做出範式轉移的貢獻,不確定你能不能感受到一種興奮,一種可以見證歷史的興奮 :)

更少人數的社交與聯邦模型

鄧巴數(Dunbar's number)是一個源自於人類學的名詞,以一種非常不科學、不精確、毫無邏輯的描述了「新皮層(Neocortex)體積」與「有意義穩定關係數量」的相關性。但它之所以廣泛流行,主要是因為它在某種程度上直觀地符合我們日常生活的經驗。

我們或許都能從自身的經驗中體會到,真正有意義、有質量的互動,往往發生在小範圍的親密群體當中。我有一些朋友,他們很少在網路上發布公開訊息,但總是在一對一或是少人數的群聊當中,發表許多有趣、幽默、新穎的見解與言論,質量好到我都有點罪惡感。這種現象並非偶然:人通常只有在一個相對舒適且安全的環境中,才能毫無保留地展現更全面的自我。這類自下而上、小規模、富有多元性且有機發展的群體,或被 Other Internet 稱作「小隊」(Squads),正在逐漸成為高品質資訊交換的重要來源。

實踐這一理念的方法之一,是透過技術手段在人數上做出明確限制。然而,從先前社交平台 Path 的經驗來看,單純在應用層強制限制好友數量的做法,成效並不理想,這樣的設計不僅限制了用戶累積社會資本的效率與能力,也犧牲了規模所帶來的效益。

另一種更有潛力的實踐方向,則是所謂的「聯邦模型」(Federation)或可稱為部落主義式的社交平台,例如前面提到的 Mastodon 或 Bluesky。我自己在理念上,也更傾向於支持此種模型。

人文學科上有《國家的視角》告訴我們,當現代政府試圖透過量化或數位化來掌控與規範被統治者的生活時,往往只是在高度複雜與多元的現實之上,創造出一種虛假的秩序感;理工學科上有複雜理論告訴我們,複雜的網路拓樸結構必然會內生的帶來新維度的複雜,以及對應產生的湧現性(Emergence),我們無法在不失去細節的前提情況下做出總結。。

然而,儘管聯邦模型在理念上頗具吸引力,其具體實踐仍須極為謹慎地設計。正如《聯邦模型世界最糟》(Federation is the Worst of all Worlds)中所警示的:

聯邦系統除了錯過了簡單中心化方案的規模優勢之外,源於其威脅模型和經濟學,最終「信任」還是會集中在少數人身上。

殘念的是,Mastodon 似乎犯了上述的毛病;而幸運的是,Bluesky 似乎對此有更深度的考量:透過將用戶的身份與數據與儲存節點解耦,利用直接訂閱帳戶的方式獲取資訊,同時引入一組可在多個資訊來源之間聚合訊息的中繼器(Relay),有效地在規模優勢與聯邦模型的自治性之間取得了平衡,進而允許平台內形成真正的跨社群、跨節點的全球對話。

結語:人類會不會就是一群追求地位的猴子?

「百年的失敗,不會在一朝一夕就能扭轉。但總要開始,而今天就是那一天。」—— 哈維爾·米雷伊

社交網絡平台的歷史相當短暫,它們的崛起不過是過去十數年間的事情。雖然多數情況下我不相信群眾的品味,但我還是樂觀的相信人類的奇蹟般的快速適應能力,以及相信短暫社交網路歷史上的諸多錯誤可以被修正。

正如《權力與進步》一書所預言的,科技與演算法正在攫取更多的政治權力,例如《非死不可——那些不管別人死活的臉書人》中提到的,2016 年川普的競選團隊正是透過臉書平台的投放,以極低的成本實現了高效的選票轉化。當扎克伯格得知此事時,他的第一反應居然是「我也能來選總統」。不用曾是屠龍的少年,也能變為欠屠的巨龍。

儘管如此,我還是固執的認為,去中心化、分布式的、強隱私抗審查的、自由的社交平台,理應被視作 21 世紀的重要基礎公共建設。然而,如何與人類的地位猴子性、實用性、娛樂性相結合,設計出次世代的社交產品,是一個極為有趣的問題,畢竟創新有風險,領先一步是先驅,領先兩步是先烈 :P