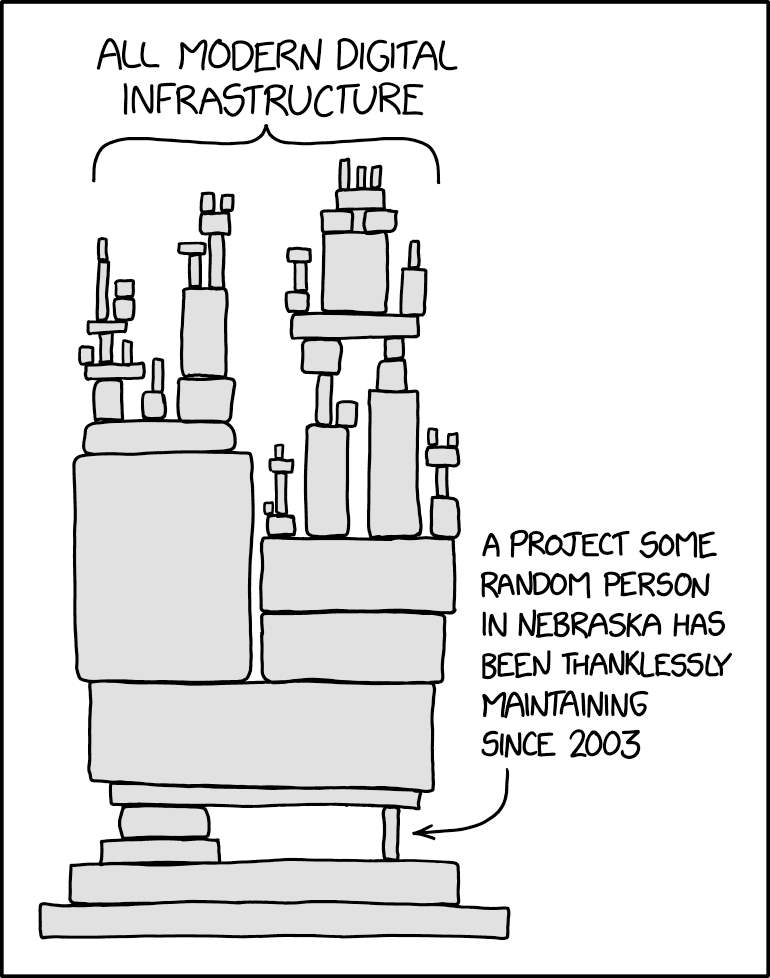

The World is Always Beautiful (If You Don't Look Closely): The Affordance of Crypto Public Goods [en/cn]

- Published on

Chinese version is available here.

"The man who dies thus rich dies disgraced." – Andrew Carnegie

One of the irresistible attractions of working in the crypto industry, especially back when I still had the stamina, was the opportunity to travel through major cities around the world, enjoying free meals and drinks. Whether it was luxurious nightclubs in Singapore’s Marina Bay Sands, sushi bars in Shibuya, hidden speakeasy in Lan Kwai Fong, or upscale Western restaurants beside infinity pools in Bangkok — armed with vaguely verifiable titles and leveraging the inflated vanity of project team, I lived like a modern-day Robin Hood, actively redistributing wealth directly to myself.

An industry flush with hot money inevitably attracts diverse participants. In my interactions, I've observed stark differences among people — so vast they seem to belong to entirely separate worlds. Borrowing Vitalik’s clear and simple categorization of industry participants as Cypherpunks, Regens, and Degens, I prefer to visualize these as three dimensions on a coordinate system, with each individual represented as a dynamic point somewhere within it.

- Degen: Views the crypto market as a giant, efficient casino—a zero-sum game.

- Regen: Believes that through technology we can create a positive‑sum world.

- Cypherpunk: More akin to anarchists who don’t care about positive or zero-sum, but simply wish not to be constrained by carefully crafted oppressive systems.

It’s worth noting that: a) These three characteristics often coexist within a single individual. b) This categorization applies to people, not projects or protocols. c) The categories themselves carry no value judgment.

I've always believed that happiness stems from abundance, so I’ve tried my best to pay unbiased attention to all three areas. Over the past few years, I've immersed myself in the intersection of crypto and public goods — partly because of passionate advocacy from friends, partly due to a sense of moral obligation, and partly out of sheer curiosity. I've met many people along the way, some of whom have become good friends. Although my enthusiasm isn’t as strong as before (attention is a scarce resource lol), I still wish to document this learning journey and my current reflections as a way of marking a personal turning point.

What is public good?

Confucian culture emphasizes the principle of "rectification of names" (必也正名乎). However, the concept of public goods among crypto practitioners is much like sex to teenagers: widely practiced yet vaguely defined.

In English, we have terms like "Public Good," "Collective Good," "Common Good," "Charity," "Public Welfare," and "Philanthropy," while in Chinese, we have terms like 公共財, 公共物品, 共有財, 公益, and 慈善. The ambiguity occurs at three levels: ambiguity within Chinese terminology, ambiguity within English terminology, and additional ambiguity introduced during Chinese-English translations. From my own reading, I've observed the following distinctions:

- "Philanthropy" typically faces less financial pressure and seeks broader impact compared to "Charity." (source)

- "Public Good" is often contrasted with "Private Good." For example, Nadia Asparouhova once remarked: “If venture capital is risk capital for private goods, philanthropy is risk capital for public goods.”

- "Public Goods" typically exhibit non-rivalry and non-excludability, whereas "Common Goods" are usually non-excludable yet rivalrous—for instance, clean air versus groundwater. (source)

- The term "Public" originates from the government, commonly known as the "Public Sector," which traditionally provides public goods to address free-rider problems.

In my conversations with LLMs (yes, I chat with my trio of assistants: ChatGPT, Gemini, and Grok to make them competitive with each other), I've come to better understand that Paul Samuelson codified the concept of "non-rivalry" in public goods, whereas James M. Buchanan and Vincent Ostrom contributed the characteristic of "non-excludability." Taking these insights together, a broader and more accurate term might be "Crypto Philanthropy," but out of respect for historical usage, I’ll continue to use the phrase "crypto public good" as an umbrella term referring broadly to ethically motivated initiatives that directly use cryptocurrencies or indirectly leverage crypto technologies.

Discussions on what precisely constitutes a crypto public good often become philosophical and hard to pin down definitively. In my view, there’s no practical need to attempt a crystal-clear definition for something inherently ambiguous. Let’s sidestep semantic pitfalls and simply adopt the approximate definition provided by the International Monetary Fund (IMF):

Public goods are those that are available to all (“nonexcludable”) and that can be enjoyed over and over again by anyone without diminishing the benefits they deliver to others (“nonrival”). The scope of public goods can be local, national, or global.

Why are blockchain technologies and public goods a natural match?

Apart from influential figures like Vitalik promoting it strongly due to his personal preferences, the core characteristics of public goods naturally align with blockchain technology. For instance, "available to all" directly translates into being "permissionless." Being usable "over and over again" aligns neatly with "composability." "Non-rival" echoes precisely the concept of "(3,3)" popularized by Olympus DAO. In other words, goods built with blockchain-based materials inherently tend to fulfill traditional definitions of public goods.

Simply put, discussions about public goods boil down to three fundamental questions:

- How can we secure funding for public-good builders? (Where does the money come from?)

- How should funds be allocated among various public-good builders and projects? (How to allocate the money?)

- How do we evaluate the effectiveness of each project? (How do we measure outcomes?)

Before the cryptocurrency era, these questions were typically answered as follows:

- Where does the money come from? The primary and most stable source of funding for public goods has traditionally been government taxation, rooted in the “social contract” tradition. To address externalities and the free-rider problem, citizens entrust funds to the government via taxes. The government then redistributes these resources through annual budgets or specialized funds to provide public goods. Additionally, charitable foundations and nonprofit organizations supplement this funding by targeting specific causes they care about.

- How should the money be spent? Government budgets usually follow clear processes: administrative branches propose budgets, which are reviewed and approved by legislative bodies. To gain legislative approval, administrations often provide feasibility studies and cost-benefit analyses. Allocation of funds across projects also involves lobbying groups and political negotiations among parties seeking to fulfill campaign promises. On the other hand, charitable foundations and nonprofits often have more flexibility. They can proactively solicit proposals, employ expert internal committees for evaluation, release milestone-based payments, or adopt participatory approaches that allow stakeholders to discuss and influence funding allocations.

- How do we measure outcomes? The method of evaluation varies according to the type of issue. For complex matters like poverty, employment, or education, we can use metrics such as poverty rates, employment levels, literacy rates, and graduation statistics to roughly quantify effectiveness through cost-benefit analyses. For more ambiguous areas like culture, art, or happiness, we often "shoot first, draw the target later"—starting with pragmatic solutions and then incrementally refining them. In the science-driven age, including numbers, formulas, regression analyses, statistical data, and graphs in reports always boosts persuasiveness. Remember, advocating for limited resources across different causes is fundamentally the art of persuasion.

These traditional methods already constituted a mature supply mechanism before crypto emerged. Today's novel technologies and mechanisms primarily enhance this traditional process by reducing coordination costs, increasing transparency, and providing immediate feedback—rather than fully replacing it.

Chess grandmaster Josh Waitzkin once suggested that to efficiently learn chess, one should start by studying endgames. Following that advice, let's first examine the relatively straightforward question of "how to allocate the money," before tackling the more challenging remaining two questions.

Three Core Questions

How to allocate the money?

Given a specific amount of money, how can we best allocate it among different public-good projects to maximize social impact?

In the crypto industry, two well-known approaches stand out:

- Retroactive Public Goods Funding (RetroPGF), as adopted by Optimism.

- Quadratic Funding (QF), used by Gitcoin.

RetroPGF tries to emulate the traditional bicameral system. Its "Token House," analogous to a House of Representatives, comprises holders of OP tokens, who theoretically have the ultimate governance authority within the Optimism ecosystem. On the other side, approximately 150 "Badgeholders" form the "Citizen House," analogous to a Senate. These Badgeholders are selected through a "Web of Trust," including appointments by the OP Foundation, elections by the Token House, previous awardees, and citizen nominations. The Citizen House directly manages the distribution and funding decisions of each RetroPGF round. Guided by the principle "impact = profit," RetroPGF rewards projects retroactively, based on their demonstrated impact.

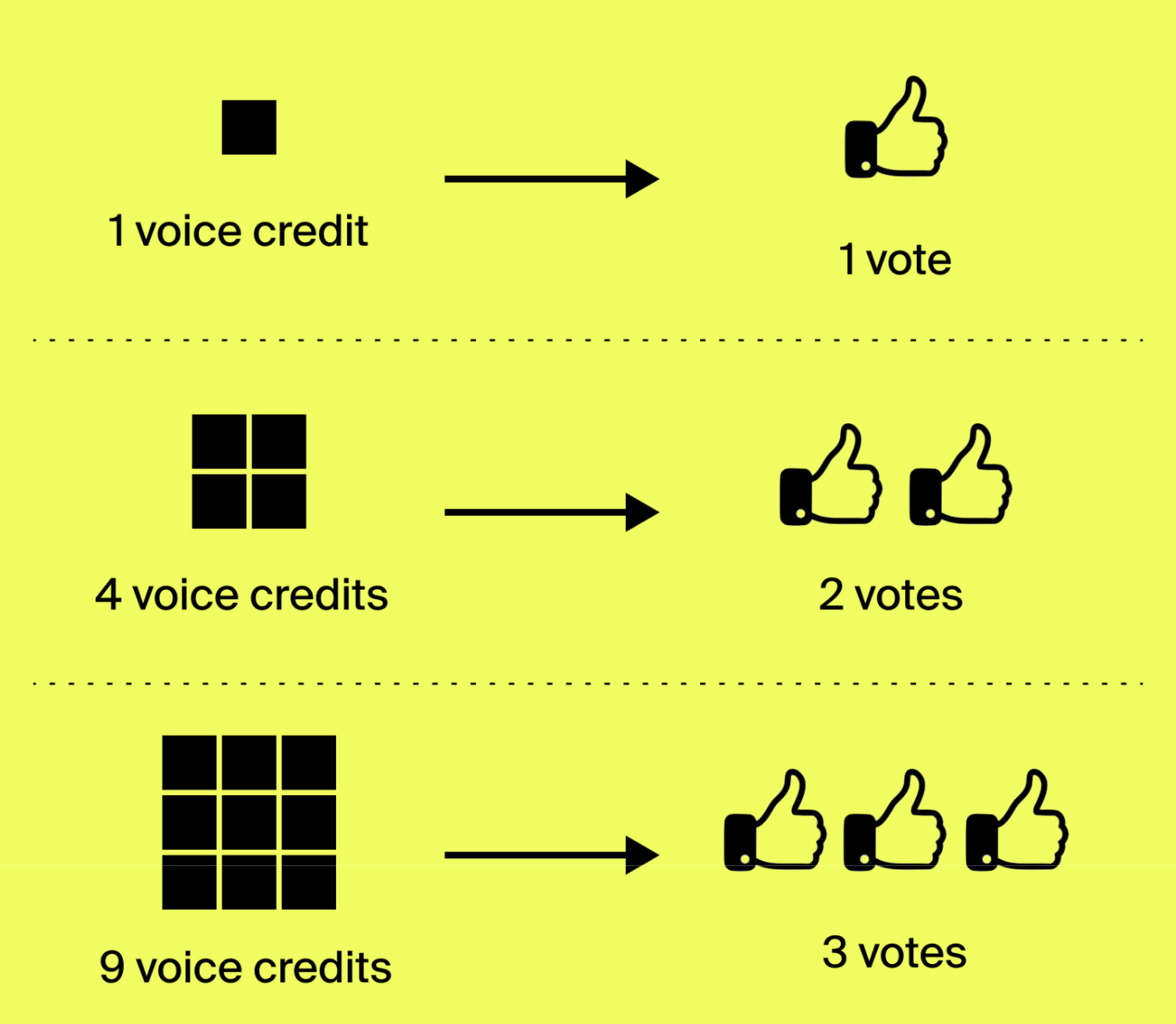

Quadratic Funding, meanwhile, requires an introduction to Quadratic Voting (QV). The origins of Quadratic Voting can be traced back to the Vickrey–Clarke–Groves (VCG) mechanism, proposed by William Vickrey, Edward H. Clarke, and Theodore Groves. The current concept gained prominence through Glen Weyl's 2012 working paper "Quadratic Vote Buying." Weyl further discussed the democratic implications with Eric Posner, and formally introduced Quadratic Voting in a 2015 paper with Steven Lalley. This academic concept gained widespread attention in crypto circles largely through the popularization efforts of the book Radical Markets and the influential paper co-authored with Vitalik Buterin, "Liberal Radicalism: A Flexible Design for Philanthropic Matching Funds."

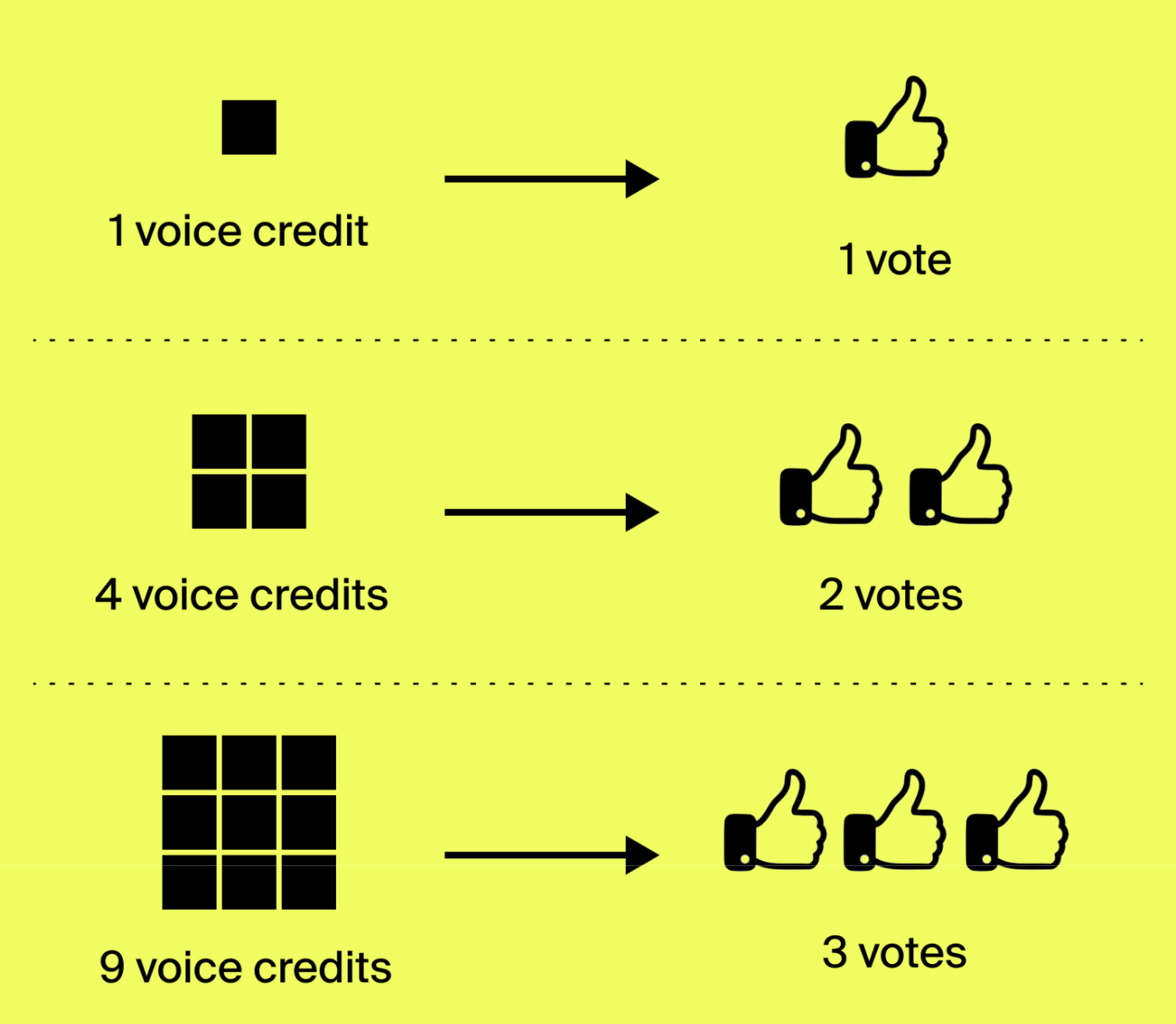

The core of QV is straightforward: voters allocate points by squaring the cost of their votes, and final results are calculated by taking the square root of the points allocated. The Economist provides an interactive webpage for intuitive exploration. Its notable advantages include:

- Allowing voters (or donors) to express preferences across multiple options.

- Discouraging "tyranny of the majority" by making it costly to heavily favor a single issue.

- Encouraging attention to neglected issues or candidates, as small allocations have proportionally greater impact.

- Promoting careful consideration through diminishing marginal returns on additional points.

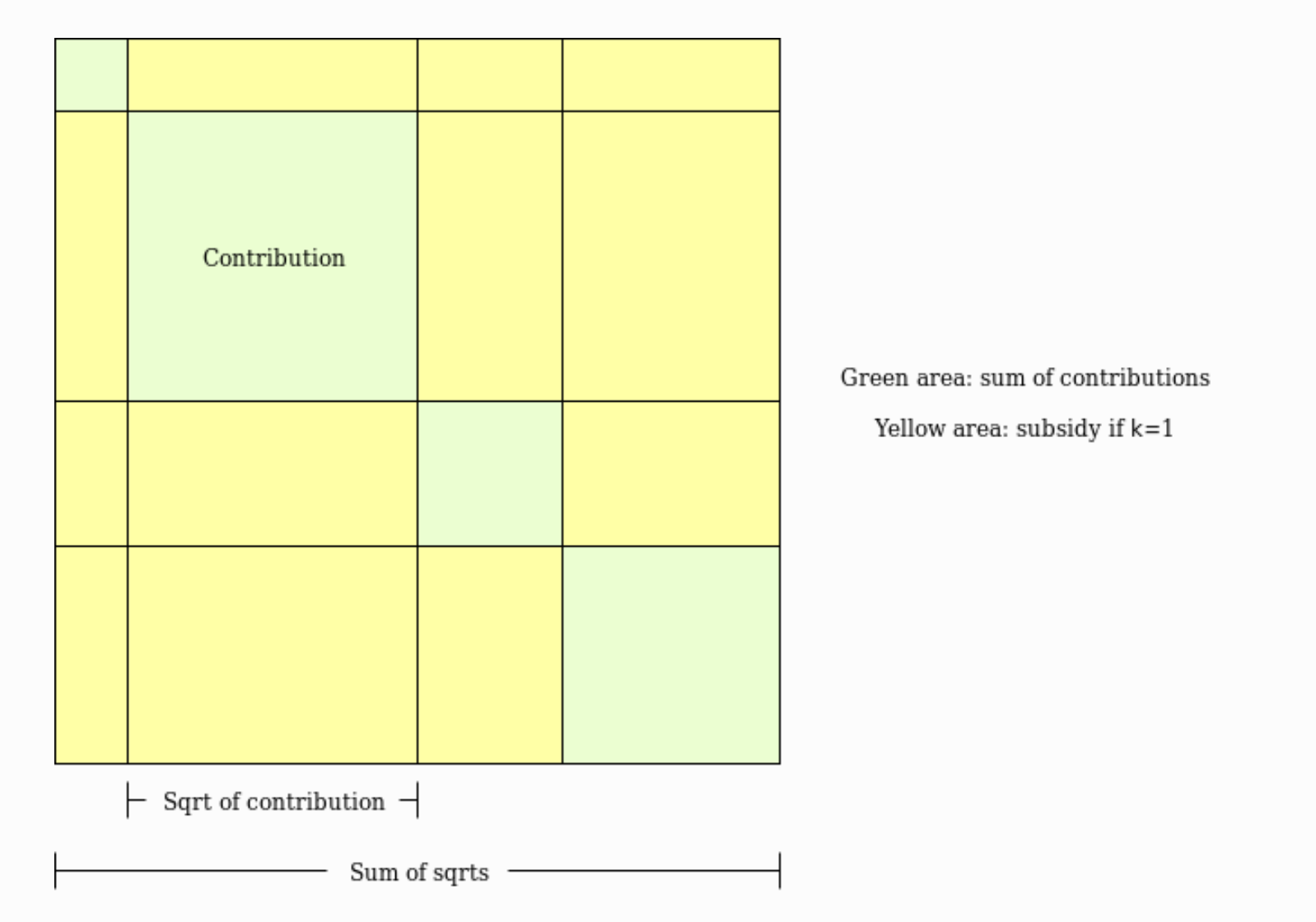

Quadratic Funding uses QV principles to allocate matching funds from a dedicated Matching Pool. From a project's perspective, funding comes from two sources: direct individual contributions and matched funds from the pool. Each individual contribution is treated as a "vote," and the amount of matching funds a project receives is calculated by taking the sum of the square roots of each individual donation amount and then squaring that sum to determine the final amount.

|

|---|

| Source: Quadratic Payments: A Primer |

A numerical example clearly demonstrates how Quadratic Funding incentivizes broader participation through small contributions:

- 10 donors each contributing $1: Each donation's square root is 1, summing to 10; squared again, this results in a matching weight of 100.

- 1 donor contributing $100: The square root of the contribution is 10, squared again, yielding the same matching weight of 100.

Notably, ten individual $1 contributions collectively trigger the same matching funds as one person donating $100. This design encourages wider participation rather than reliance on fewer large donors. To see this mechanism in action, you can explore Gitcoin’s dedicated website (near the bottom of the page). Beyond Gitcoin, virtually all current crypto-based donation platforms, such as Endaoment and Giveth, have adopted similar concepts to varying degrees.

Note: Introducing a single mechanism doesn't usually suffice academically to establish a distinct school of thought. Glen Weyl and Audrey Tang (AU) thus proposed the broader concept of "Plurality," rebranding Quadratic Voting as "Plural Voting" and Quadratic Funding as "Plural Funding." Practically, these renamed concepts are essentially identical. For those interested, more detailed explanations are available through the official open-source book and this comprehensive overview.

Challenges and Solutions

Quadratic Funding faces two prominent types of attack vectors: Sybil attacks and participant collusion.

A Sybil attack refers to a single individual creating multiple accounts to make numerous small donations, artificially amplifying their influence and undermining the entire Quadratic Funding mechanism. Typically, this is countered using some form of Proof of Personhood, which can rely on biometric identification techniques, such as the iris scanning technology used by Worldcoin, or social graph-based verification, like Gitcoin Passport (recently rebranded as "Human Passport," though personally, I prefer the old name).

Participant collusion usually manifests when influential community figures promote or endorse projects closely linked to themselves on social media, rallying followers to collectively support these projects (jokingly referred to by friends and me as "The Rumbling"). Morally, this isn't inherently wrong—similar tactics exist in democratic political campaigns—but it can lead participants to blindly follow leaders without genuinely understanding the projects involved. Consequently, this reduces the quality of matched funds allocation, making the whole mechanism appear as an influence game.

To address these issues, a group of idealistically-minded researchers embracing the notion of "Plural Cybernetics" (a term I just coined) have proposed computational refinements. Their improvement strategies include:

- If two donors display very similar donation patterns, this indicates potential collusion, warranting a certain penalty.

- Projects receiving broad, diverse community support likely have higher universal appeal, aligning closely with the spirit of "public" goods, warranting a reward.

Two main variations of refined Quadratic Funding following this logic have emerged:

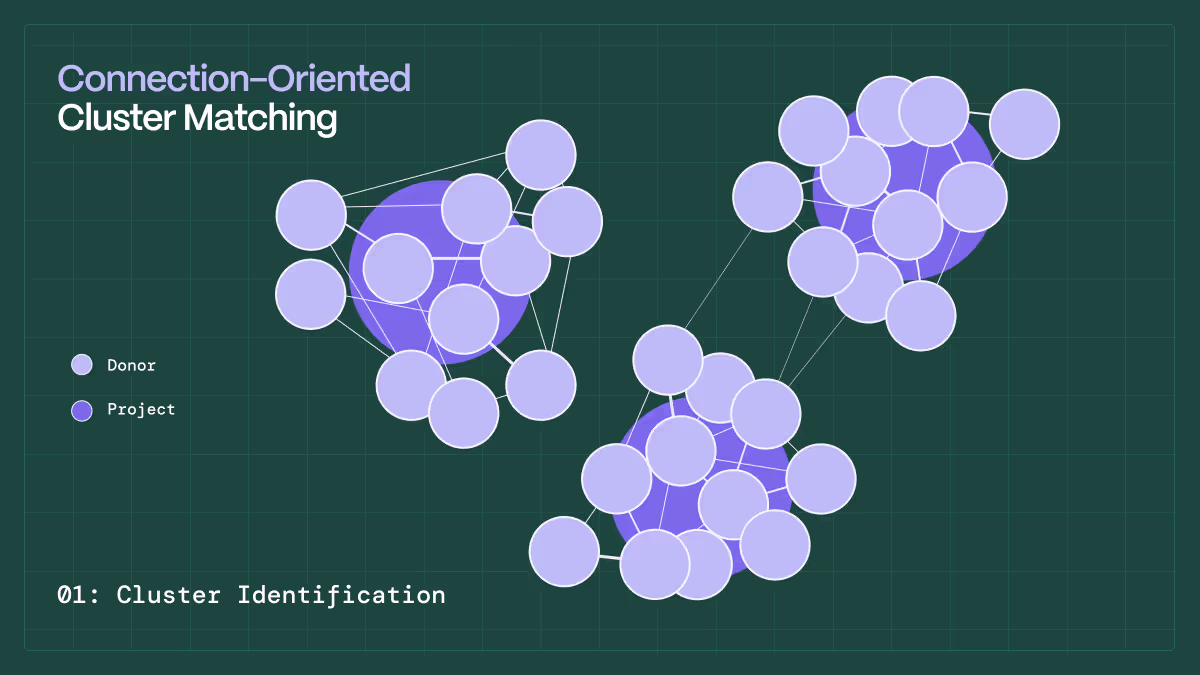

- Pairwise Quadratic Funding (Pairwise QF): Directly considers similarity between pairs of donors’ donation patterns, making calculations relatively straightforward.

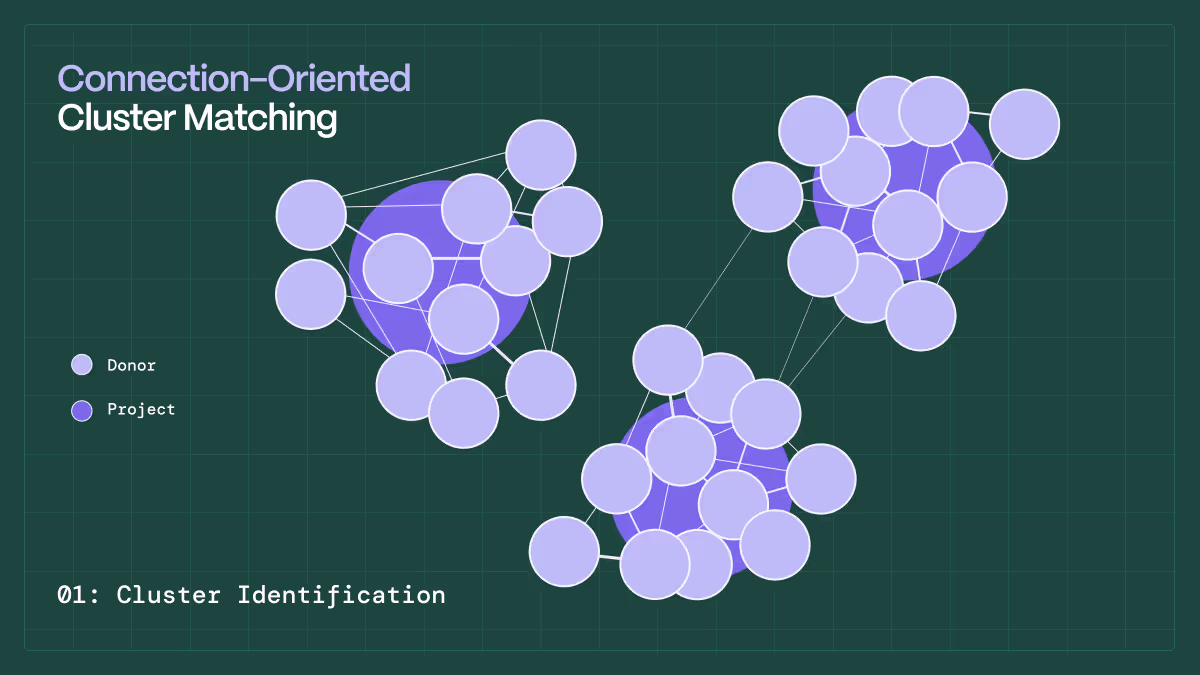

- Connection-Oriented Cluster Match (COCM): Attempts to identify and segment distinct donor subgroups at a broader scale.

Of course, theoretically, these two approaches can be combined to counteract community-level collusion effectively. Gitcoin currently employs COCM (I’m still puzzled why public good bros seem so fascinated with the term “wtf”), claiming a 50% improvement over previous methods—though personally, I’ve not seen clear evidence backing this figure. You can explore Python implementations of QF, Pairwise QF, and COCM here, and experience these mechanisms interactively here. It's worth noting that clustering methods fall under traditional machine learning research, and the referenced implementations demonstrate three different clustering approaches.

|

|---|

| Source: Gitcoin Blog |

Supplementary note: There's an entirely different funding mechanism called Deep Funding, unrelated to the above methods. Its core idea is leveraging an explicit dependency graph combined with Distilled Human Judgment (DHJ)—an AI approach that translates human judgments into forms comprehensible to AI to improve decision accuracy. Because Deep Funding requires a clear dependency graph (such as project-forking relationships on GitHub), its applicability is somewhat limited, though it enables more precise quantitative evaluations. Deep Funding remains experimental; you can read an introductory article here or observe this latest experimental funding round.

How to Evaluate Outcomes?

As donors, how can we better judge who deserves our support and who doesn’t? Who is merely all talk, and who genuinely delivers? This is an age-old challenge in traditional philanthropy, and the crypto community has yet to propose groundbreaking insights for quantifying impact (perhaps because there never was a universally correct solution). However, thanks to the characteristics of the "world computer," we can reduce coordination costs among donors, enhance transparency of fund flows, strengthen immediate feedback mechanisms, and make donation rules clearer and more trustworthy.

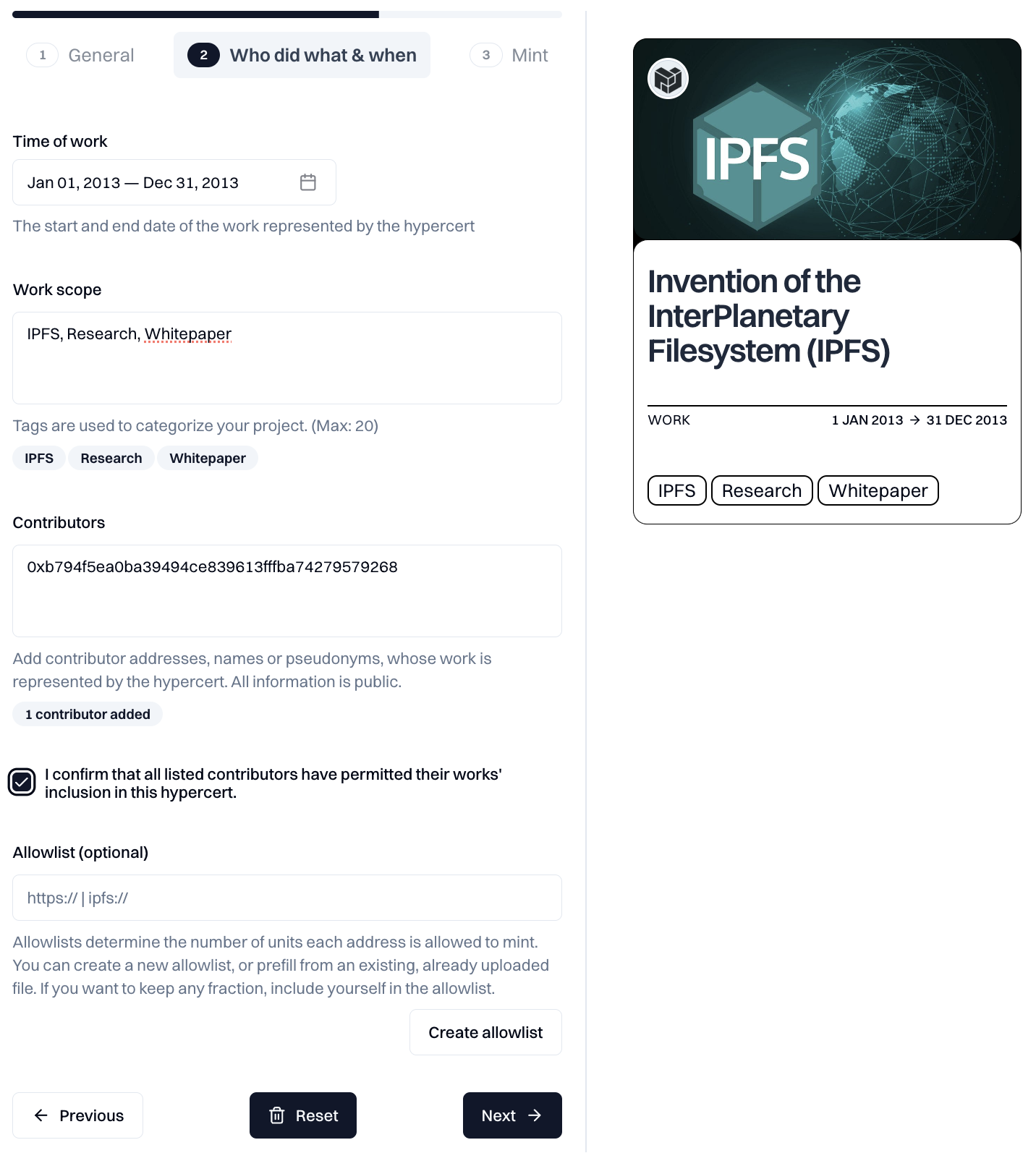

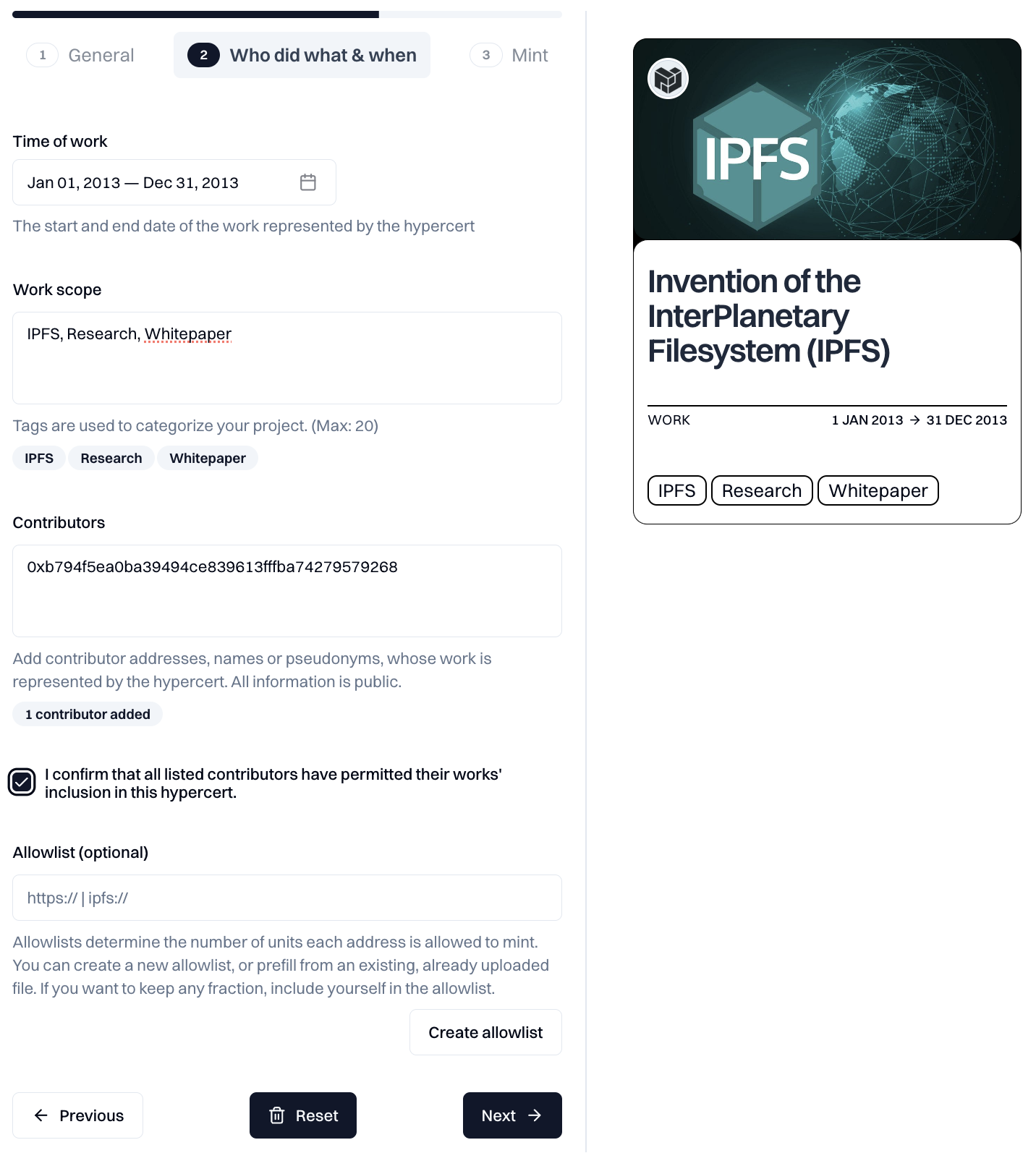

The most frequently discussed example is the Hypercerts specification proposed by the Hypercerts Foundation, supported by Protocol Labs. Essentially, Hypercerts are open-format certificates recording contributors' wallet addresses, the proportion of their contributions, timestamps, and details about their contributions. Hypercerts are ERC-1155 tokens currently deployed on the OP Chain—a public goods friendly network—with their data stored in JSON format on IPFS. Supporters can acquire Hypercerts in the primary market through a "purchase-as-support" approach, with funds typically distributed among contributors according to predetermined ratios.

Ideally, public-good contributors can issue Hypercerts in advance to raise seed funding for their projects, allowing early supporters to buy them at lower prices. When a project is completed or demonstrates significant social impact, organizations with ESG objectives can purchase Hypercerts in secondary market, creating a win-win-win scenario: organizations receive credible ESG credentials backed by real-world contributions; early supporters profit from the increased value of Hypercerts; and contributors secure funding while retaining project ownership/credit.

However, due possibly to regulatory complexities, a robust secondary market for Hypercerts does not yet exist.

Where Does the Money Initially Come From?

Finally—and perhaps most fundamentally—where does the money come from? Let’s first examine some specific examples:

Gitcoin, a leading figure in crypto public goods, has diverse funding sources for its matching pool. Contributors include the Ethereum Foundation (EF), Gitcoin DAO, Uniswap DAO, Polygon Foundation, ConsenSys, Yearn Finance, Chainlink, dYdX, PoolTogether, Coinbase, Mask Network, Protocol Labs, Celo Foundation, 0xPARC, ENS, 1inch DAO, and various other foundations and projects. Additionally, there are a few generous individual philanthropists who provide direct sponsorship.

Endaoment’s matching pool funding is primarily replenished by Gitcoin and its community donors. Giveth’s funding comes from organizations such as Nouns DAO, ENS DAO, Octant, Aragon, and Arbitrum. Meanwhile, Optimism RetroPGF’s funding relies on support from the Optimism Foundation, initial token allocations, and revenue generated by the centralized Sequencer—a role responsible for transaction ordering.

From these examples, it becomes clear that foundations or projects (in my view, there’s little practical distinction between the two) frequently leverage tokens under their control as resources. This practice resembles the way projects use token airdrops to attract early users, incentivizing contributors to build within their ecosystems. Foundations operate much like drivers, carefully managing the throttle to achieve the best pace and maximize their distance traveled.

Having reflected on these three core questions, I’d like to share a few thoughts:

- Practicality of COCM: In my experience, COCM is genuinely effective. Before the implementation of COCM, my friends and I once attempted to exploit a funding round in Taipei. Although we achieved notable paper results, Gitcoin’s mechanism incorporates a "Fund Manager" role, who retains ultimate discretion over allocations. In reality, they manually adjusted distributions directly via a CSV file, neutralizing our efforts and rendering that particular funding round unsuccessful. Under COCM, I tested the same tactic and found it ineffective.

- Priority of Core Issues: I believe the questions "Where does the money come from?" and "How do we measure outcomes?" are more fundamental and critical. Yet within the crypto public goods community, discussions about "how to allocate the capital" dominate the conversation. This is understandable—allocation mechanisms are clearer and more concrete, providing immediate satisfaction through technical improvements and iterative refinements. However, such incremental optimizations have their limits, and we've already had extensive (perhaps excessively extensive) debates about them. Having mastered the art of cake-slicing, we should now shift our focus to the more critical challenge of enlarging the cake itself.

- Defining Public Goods: Exactly how "public" should a public good be? Should projects clearly benefiting specific groups participate in broader ecosystem matching pools? Can Layer 1 resources legitimately sponsor Layer 2 initiatives? What are the shared community values? Who constitutes the community, and who benefits from a given public good? These foundational questions might be difficult to answer, but eventually we must confront them. Those who've experienced democratic elections understand well that democracy's true essence lies not in the act of voting itself but in the dialogue, negotiation, and debate with voters beforehand.

- The Power of Narratives: Whether through negotiation or brainwashing communities (note: I use terms like "brainwashing" and "cult-like" neutrally), public goods currently function largely as an influence game—and that’s acceptable. After all, consensus and shared values typically emerge this way. Narratives are critical assets that must be actively acquired. As Yuval Harari argued in Sapiens, stories provide the foundational basis for human collaboration. This field is nascent and will require proactive leadership. Historically, new movements often begin under leaders whose charisma borders on cult-like influence. Fortunately, at present, we have benevolent figures like Vitalik and Owocki guiding us. As the old saying goes, "The hardest thing in the world is getting someone else’s money into your pocket—or your ideas into someone else’s head." Crypto public goods grapple simultaneously with these two formidable challenges.

Dive into sustainability

"In theory, there is no difference between theory and practice. In practice, there is." — Yogi Berra

Sustainability has always been an open secret deeply hidden within the crypto public goods sector—rarely talked about openly. I once created a small project called "Taiwan HyperAwesome Guidebook." At the time, we attempted to hide Quadratic Funding’s somewhat intimidating complexity and adapt human-driven Web of Trust. We even introduced a "one-pulls-two" incentive structure resembling a multilevel marketing scheme to encourage participation. Yet, nearly a year after launch, due to insufficient motivation among participants, there remain only a pitiful three projects listed on our website. This firsthand experience made me keenly aware of just how difficult sustainability is, especially when driven by goodwill alone.

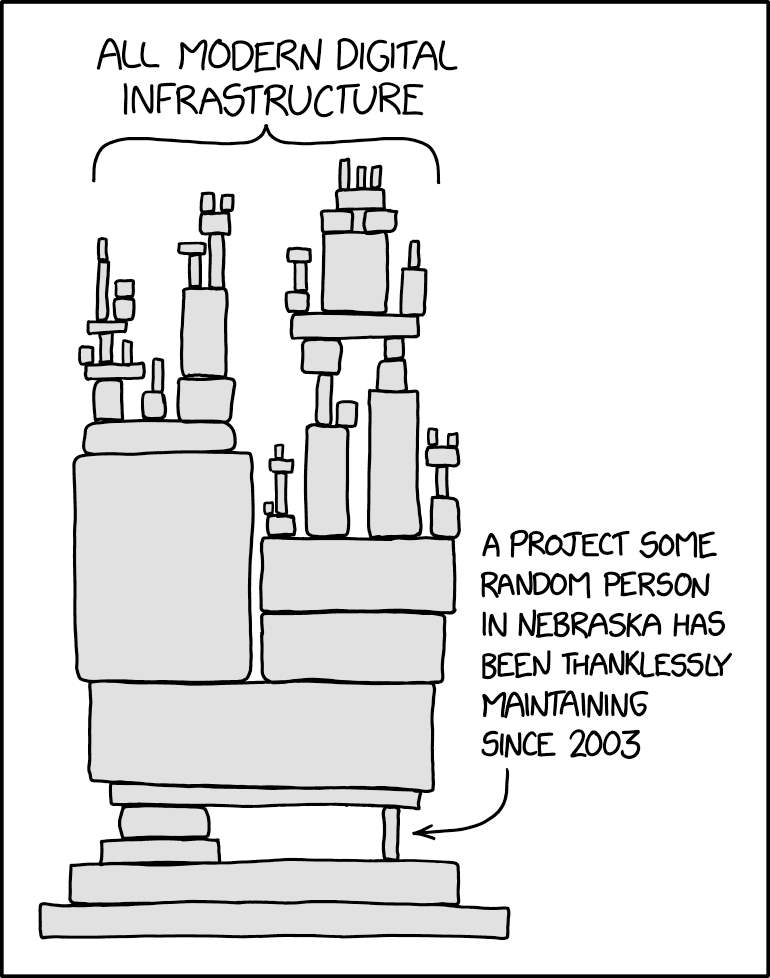

If you carefully scan the Gitcoin or RetroPGF community forums, you’ll quickly notice many public goods contributors expressing frustration over funding instability. The unpredictable funding size, direction, and terms of each funding round create significant uncertainty in income expectations, causing hesitation to fully commit to projects. Imagine choosing between endless, uncertain fundraising cycles or directly developing a product that can immediately attract funding and issue tokens. Even those with a strong moral compass will struggle when faced with such a stark choice.

Currently, the most viable solution to the sustainability problem seems to draw inspiration from real-world governments: using taxes to finance public goods rather than relying on the inconsistent goodwill of foundations or projects. My friend Taka boldly claims, "Taxation as an endgame," and I personally share this viewpoint.

If we imagine Ethereum as a network state, then smart contracts constitute its legal system. In theory, we could embed funding for public goods directly into the core of the protocol itself—specifically through Ethereum Improvement Proposals (EIPs). But the critical question then arises: Where exactly should this funding originate from? This deserves deeper exploration.

Taking Ethereum as an example and viewing it through the lens of Total Economic Value (TEV), we find three primary potential funding sources: Network Fees, MEV Tips, and Issuance. Here's an analysis of these three options:

- Network Fees: Since the implementation of EIP-1559, network fees are composed of two parts: the Base Fee and the Priority Fee (or bribe fee imo). Priority Fees are directly give to proposers, while Base Fees are burned, creating deflationary pressure on ETH’s supply. Base Fees are relatively stable, and their amount grows as Ethereum usage increases. However, redirecting Base Fees toward public goods instead of burning them could weaken some users’ confidence in Ether as an "Ultrasound Money" asset. Such users value ETH primarily for its scarcity, and altering the burning mechanism might provoke controversy.

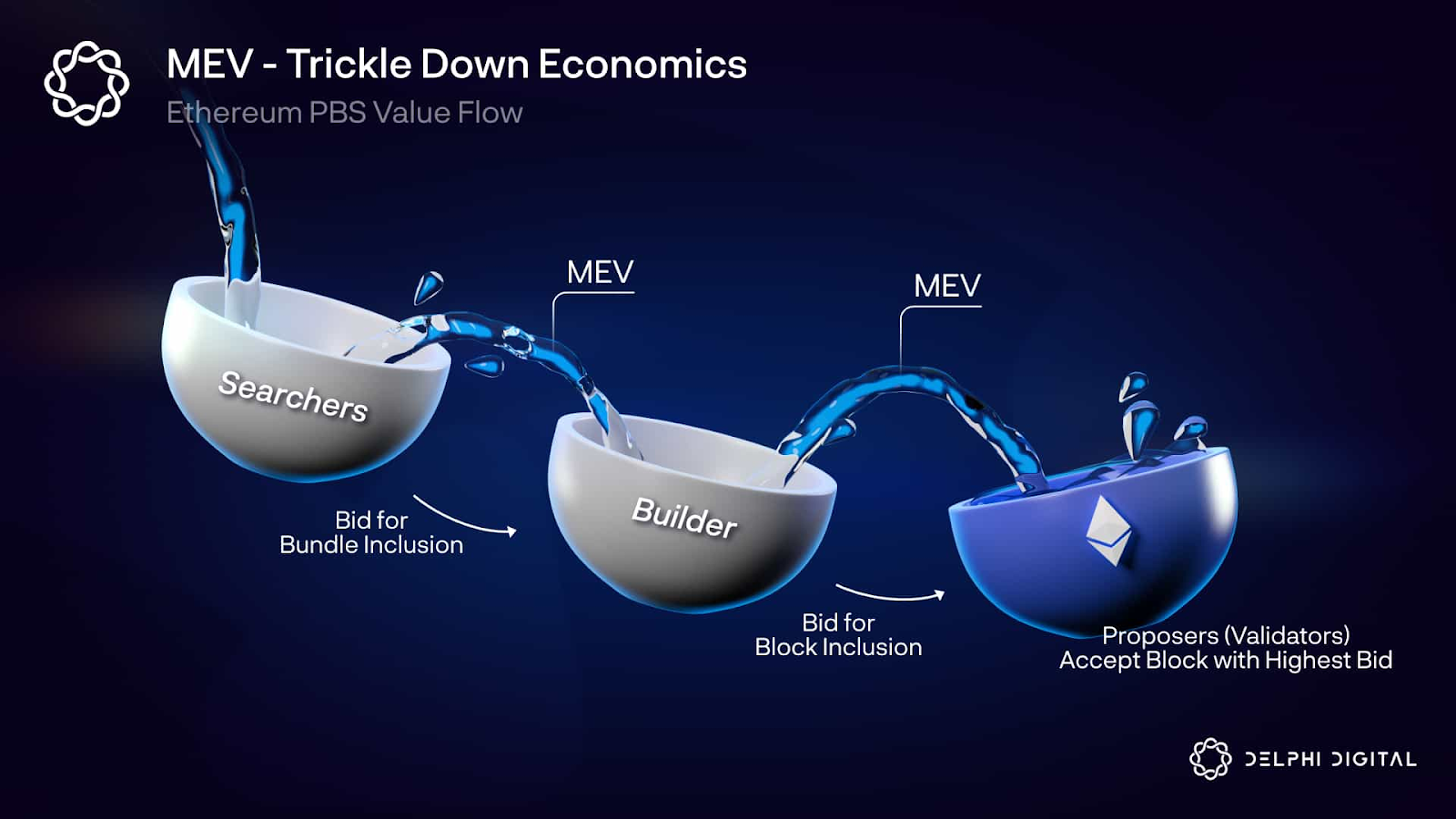

- MEV Tips: Under PBS (Proposer-Builder Separation), MEV Tips are fees that block builders pay to proposers in exchange for advantageous transaction ordering. A downside is that MEV revenue is volatile, depending heavily on market activity and competitive dynamics. Additionally, MEV itself is a complex strategic game, and introducing new rules might disrupt the existing balance. On the upside, MEV Tips typically generate substantial revenue. If PBS were embedded directly into Ethereum’s core protocol (known as enshrined PBS, or ePBS), it could formalize the redirection of MEV revenues toward public goods funding, lending this method significant legitimacy. (Note: Builders are responsible for optimizing the block, usually requiring specialized knowledge, while proposers initiate consensus and earn Ethereum’s PoS rewards. In practice, almost all proposers outsource block-building through MEV-Boost to three dominant builders: Beaver, Titan, and rsync.)

- Issuance: This involves newly minted ETH issued as rewards to validators to incentivize network security. The advantage is long-term stability and predictability. However, the downside is that issuance competes directly with validators’ rewards, indirectly undermining network security. Additional issuance would alter Ethereum’s monetary policy, potentially leading to inflation, contradicting its current deflationary trend.

|

|---|

| Source: The Complete Guide to Rollups |

Considering the analysis above, the optimal funding source likely involves leveraging ePBS to divert a portion of MEV revenues toward public goods. This approach can provide substantial funding without directly disrupting Ethereum’s economic balance, such as its deflationary mechanisms or validator incentives. Additionally, treasury funds from DeFi DAOs can serve as a supplementary source. By supporting public goods through community governance, these DAOs can align themselves more closely with Ethereum’s broader narrative and achieve its public-relations goals, creating a beneficial win-win situation for the whole Ethereum ecosystem.

Affordance of Crypto-Enabled Philanthropy

Finally, let’s step away from the clichés above and discuss crypto public goods from a fresh angle. I’ve been contemplating the fundamental ways blockchain technology can benefit charitable and public-good efforts—in other words, how can we genuinely create a bigger pie?

Here are some directions I’ve considered. Each has its challenges and varying degrees of feasibility, but I’m offering them to spark dialogue, inject some productive noise and collectively search for ways to break out of our current saddle points.

- Seamless Micro-Donations: Right now, the only universally acknowledged product-market fit for crypto is maintaining a digital number peg to 1 — or stablecoin if you prefer. If blockchain could evolve into an ideal financial payment layer, minimal transaction fees and instant settlement would enable effortless global micro-donations to virtually any cause (provided it has a wallet address). Imagine a universal, crypto-enabled Alipay. See a beautiful mural that brightens your day? A small crypto-address QR code in the corner lets you tip 10 cents within five seconds. Deeply moved by a wildlife documentary? Quickly find Serengeti National Park’s crypto wallet address and instantly translate your emotions into action. I suspect, albeit without any evidence, that donation willingness rises exponentially as amounts drop below a certain psychological threshold. This would not only lower donation friction but also allow goodwill to flow globally in real-time, magnifying collective philanthropic impact.

- Flywheel of Transparency, Tax Deductibility, Accountability, and Increased Donation Willingness: It’s uncertain whether causality exists here, but there’s a clear correlation between tax-deductible donations and individuals’ willingness to donate. Many crypto donation platforms have not yet scaled, likely because they lack complementary tax incentives. Blockchain’s inherent transparency ensures every donation is permanently recorded, making accountability clearer and reducing opportunities for misuse. Speaking personally, knowing exactly how my funds are being utilized greatly increases my motivation to donate. Additionally, nonprofit organizations typically must adhere to rigorous transparency standards, submitting annual financial reports to the public and tax authorities. Blockchain can significantly streamline and enhance compliance with these transparency requirements. (Realistically, nonprofits would benefit most by accepting stablecoin donations, as token volatility poses significant accounting challenges for organizations lacking specialized accounting expertise.)

- Leveraging Meme Culture, FOMO, and Gamification: Instead of passively awaiting handouts from meme-token projects, proactively harnessing meme culture, leveraging FOMO, and designing status games can effectively advance public goods initiatives. A prime example is the Armstrong Foundation’s Livestrong bracelets, combining charity with social status. In Taiwan, the previously popular "charity pens" turned out to be pure scams and don’t fit into this category. Better examples include advisory IDs issued by police stations or FAB DAO’s NFT donation certificates. Although past controversial (and perhaps unsuccessful) cases like SciHub and “Lee Lao-Shi Isn’t Your Teacher” have caused community uproar, I believe that if packaged correctly, these tactics could become powerful.

- Metaverse and AI Agents: Whether we call it the "Metaverse" or not, it’s clear that a world filled with AI agents is rapidly approaching. Public goods will increasingly be produced and delivered by AI agents—for instance, providing highly precise weather forecasts down to a few square kilometers and a three-hour timeframe. Imagine AI agents in the Metaverse like hotel doormen who valet your car, open doors, and carry your luggage; etiquette suggests we might tip them depending on our mood. But more fundamentally, AI agents aren’t free: computational resources, API calls, large-model operations, database access, and customization all incur costs. Even silicon-based lifeforms can't run indefinitely without fuel. How can we handle these frequent, small-value transactions effectively? Blockchain technology could provide a perfect payment layer for precisely this type of scenario.

Closing

"The world is always beautiful, if you don’t look closely." — Modern Cinema Master

This article has examined crypto public goods from a relatively narrow perspective. Many significant issues remain untouched, including:

- The Principal-Agent Problem: Even after successfully mobilizing donations for public goods, there's typically still a need for roles similar to fund managers to allocate resources effectively. How do we address challenges inherent in these principal-agent relationships? How can we identify the most suitable managers who possess genuine local expertise? Can these agents be held accountable, and if so, how should accountability mechanisms be designed?

- International Cooperation: How can international funding platforms better learn from and integrate the valuable experiences of local grassroot organizations?

- Trade-offs in Wealth Generation and Redistribution: How do we properly evaluate the societal harm caused by wealth extraction against the societal benefits created by redistributing wealth? (This issue lies at the heart of effective altruism.)

- Clearer Definitions of Public Goods: Apart from "Free and Open Source Software (FOSS)," can we clearly define and quantify other types of public goods?

- Defining "Publicness": How exactly should we define the "publicness" aspect of public goods, and how can we establish shared values across communities?

- Scale and Effectiveness: Is a larger scale always beneficial? Does increasing scale necessarily translate into greater positive externality?

Regarding crypto public goods, numerous shortcomings and unresolved questions remain. However, many of these issues cannot be rushed. Culture evolves incrementally across generations, and public good culture can indeed progress—from being driven purely by moral obligation to being guided by clear mission and values; from spontaneous individual acts to systematic, professional, long-term efforts; and from benefiting primarily local and personally connected groups to serving countless distant strangers. Public goods represent a discipline scattered with ambitious ideals, and only by maintaining incurable optimism can we continually move forward.

世界永遠美麗只要你不在意:加密公共財的可能性

「富裕至死,極其可恥」 – 安德魯·卡內基

對於當時還有體力的我來說,在加密貨幣產業工作其中一個致命的吸引力,是能穿梭全世界各大都市,到處的騙吃騙喝。無論是新加坡濱海灣金沙內的奢華夜店、東京澀谷的壽司店、香港蘭桂坊的隱藏雞尾酒酒吧、曼谷無邊際泳池旁的高檔西式餐廳,依靠著不好檢驗真偽的頭銜,以及項目方過度通膨的虛榮心,我像個現代的羅賓漢一樣,身體力行的劫富濟自己。

熱錢湧動的產業注定吸引到各式各樣的參與者,在與人打交道過程中,我發現人與人差異之巨大,幾乎是兩個不同世界的人。沿用 Vitalik 將從業者簡易但清楚分類為 Cypherpunk、Regen、Degen 三種類型,我習慣將這三種特質視為座標系的三個維度,每個人都是在其中的一個動態的點。

- Degen:將加密貨幣市場視為一個巨大的有效率的賭場,零和遊戲。

- Regen:相信透過技術,我們可以產生一個正和世界。

- Cypherpunk:更像一群無政府主義者,不管正和零和,只求不被精心設計的邪惡體系束縛。

值得注意的是,a) 三種特徵常混合在一個人身上 b) 這是對「人」的分類而非專案/協議 c) 特徵是不帶價值觀判斷的。

我一直相信幸福來自於豐饒,所以盡量不帶偏見地同時關注三個領域。過去兩三年,我投入「公共財 × 加密貨幣」領域,部分源於好友的熱情傳銷,部分出於良善道德感,部分純粹好奇。我認識了很多人,也交了一些好朋友。雖然如今不再像以前那樣熱衷(注意力是稀缺資源),但仍想記錄這趟學習旅程與當前看法,作為階段性道別。

何謂公共財?

儒家文化有「必也正名乎」的傳統,但公共財之於加密貨幣從業者,正如性愛之於青少年:多數人整天在用,具體定義卻模糊。

英文有 Public Good、Collective Good、Common Good、Charity、Public Welfare、Philanthropy;中文則有公共財、公共物品、共有財、公益、慈善。模糊是三重的:中文自身模糊、英文自身模糊、中英對照與翻譯上的交叉模糊。在我閱讀不同資料給我留下的印象有:

- Philanthropy 比 Charity 更無收入壓力、更追求影響力。(來源)

- Public Good 是相對於 Private Good 的,例如 Nadia Asparouhova 曾說過:「如果風險投資是為私有財提供的風險資本,那麼慈善事業就是為公共財提供的風險資本。」

- Public Good 通常需「非競爭性」(non‑rival)與「非排他性」(non‑excludable);相對的 Common Good 通常非排他、卻競爭性,例如乾淨空氣 vs. 地下水。(來源)

- 「公」源自政府通常被稱為「公部門」,傳統上公共財需由公部門提供以解搭便車問題。

與 LLMs 的對話中(恩,我習慣同時使用 ChatGPT、Gemini、Grok 這三位助手),我進一步了解到,是由 Paul Samuelson 規範了公共財的非競爭性質,而 James Buchanan 和 Vincent Ostrom 則賦予了非排他性特徵。綜合來看,更好更廣泛的稱呼是加密慈善或加密公益,但出於對歷史的尊重,接下來我會用「加密公共財」這個詞,來代指此類型直接使用加密貨幣,或間接使用加密貨幣技術來做道德上好事的統稱。

關於加密公共財究竟是什麼的討論,往往容易變得很哲學,難有定論。試圖為本質模糊之物下清晰定義,在我看來沒有必要。先讓我們擺脫語意陷阱,簡單的直接使用國際貨幣基金組織給的概略性定義:

「公共財是指那些對所有人都可用的(“不可排他”),並且可以被任何人一再享用,而不會減少它們為他人帶來的利益(“非競爭性”)。公共財的範圍可以是地方性的、國家級的或全球性的。」

為什麼區塊鏈技術與公共財是天生一對?

除了像 Vitalik 這樣的意見領袖因個人偏好而強力推廣之外,根據上述的定義,我們可以發現,公共財的核心特徵與加密貨幣相當契合。例如,對所有人都可以用(available to all)不就是無需許可(permissionless)嗎?一再重複使用(over and over again)不就是可組合性(composable)嗎?非競爭性(non-rival)不就是 Olympus 談的(3,3)嗎?換句話來說,使用區塊鏈這種類型的材料打造的物品,天生容易符合公共財的傳統定義。

簡單來說,關於公共財的討論,我們是在討論這三個問題:

- 如何找到一筆資金來給到公共財建設者?(錢從哪裡來)

- 有資金之後怎麼在不同的公共財建設者與專案項目之間分配?(錢怎麼花)

- 如何評估每個專案項目各自的成效?(成效怎麼看)

在前加密貨幣時代,這些問題通常是這樣解決的:

- 錢從哪裡來: 公共財最主要且最穩定的資金來源是政府稅收。這延續了社會契約的傳統:為了應對外部性與搭便車問題,人民透過稅的形式交付政府資金,再由政府統一透過年度預算與專項基金的形式,為人民提供公共財。另外,慈善基金會與非營利組織則作為補充,提供資金給自身關注的議題。

- 錢怎麼花: 政府預算通常有明確的流程,例如由行政部門編列預算,由立法機關審核通過。行政部門為了取信立法機關,通常會附上可行性研究、成本效益分析。在不同項目之間的資金分配方面,則會有遊說團體在其中斡旋,各政黨也會進行政治協商,來試圖兌現自己競選時開的口頭支票。另一方面,慈善基金會與非營利組織則有機會更靈活操作,例如可以主動邀請提案、由內部專家委員會評估、採用里程碑式撥款,或用參與式的方式,讓相關利益者來討論與決定資金流向。

- 成效怎麼看: 根據不同的問題類型,通常有不同的評估方式。例如貧窮、就業、教育等複雜議題,我們仍可間接使用貧窮人口佔比、就業率、識字率、畢業率等數字粗略量化,進行所謂的成本效益分析。對於文化、藝術、幸福程度等更模糊的領域,則常先射箭再畫靶,也就是先有一套「務實」的解決方式,再局部優化這個解方。在科學當道的當下,在報告中加入一些數字、公式、回歸、統計數據、圖表,總是能增加說服力;別忘了,在不同的議題之間爭取有限的資源,是一門關於說服的藝術。

這些傳統方法在加密貨幣技術出現之前,已然有一套完整的供給機制;今日的新技術和機制多半是在降低協調成本、提升透明度與強化即時回饋的基礎上,對上述傳統流程進行補強,而非完全替代。

西洋棋大師 Josh Waitzkin 曾建議,如果想要更有效率地學習西洋棋,可以從學解殘局開始。有樣學樣,先讓我們來看「錢怎麼花」這題比較明確的,再去談相對困難的另外兩題。

核心三問

錢怎麼花

在給定一筆資金的情況下,我們該如何挹注到不同公共財專案,才能產生更大的社會影響力?

區塊鏈產業有兩套比較知名的做法有 a) Optimism 採用的回溯性資助(Retroactive Public Goods Funding,RetroPGF) b) Gitcoin 採用的平方募資法。

RetroPGF 試圖效仿傳統的雙院制(Bicameral System):眾議院(Token House)是 OP 代幣的持有者,理論上對 Optimism 的治理有最終的話語權;元老(Badgeholder)約150位,透過 OP 基金會指派、眾議院選舉、過往獲獎者及公民推薦等「信任網絡」產生。元老院(Citizen House)則直接負責每一輪次 RetroPGF 的資助方向與具體分配結果。秉持「影響力 = 利潤」的指導性原則,「事後」依影響力給予獎勵。

平方募資法則需要先介紹平方投票法。平方投票法最早可以追溯到由 William Vickrey、Edward Clarke 和 Theodore Groves 提出的 VCG 機制;當下提及的版本,最早是由衛谷倫(Glen Weyl) 在2012年一篇名為〈Quadratic Vote Buying〉的草稿中提出,隨後與 Eric Posner 討論探討其在民主政治的意涵,並於 2015 與 Steven Lalley 正式發表〈平方投票法〉論文。這個學術的內容之所以在加密貨幣圈走紅,主要因《激進市場》科普書的問世,以及與 Vitalik 合寫的《自由激進主義》。

其核心其實很簡單:先平方換成點數,分配後再開根號計票。經濟學人提供的互動網站可直觀體驗。常見優點有:

- 允許選民(或捐款人)在不同選項間表達偏好;

- 把所有點數灌在單一議題成本高,可抑制多數暴政;

- 小額點數效益最高,鼓勵關注原本被忽視的議題/候選人;

- 點數邊際效益遞減,促使更深思熟慮審慎的點數分配。

平方募資法是一種使用平方投票法來決定配對「資金池」分配的機制。從被資助項目的角度來看,收入主要有兩種來源:「個人直接捐款」與「資金池的配對」。每筆個人捐款被視為一種「投票」,而項目能獲得多少資金池配對資金的權重,則是先將每筆個人捐款金額開平方根(sqrt of contribution),相加(sum of sqrts),再平方(整塊的面積)。

用數字來看,也能直觀地感受到整套平方募資機制是如何鼓勵更多人參與小額捐款的:

- 10人各捐1元:每筆捐款的平方根為1,10次相加後平方根和為10,平方後為100(從資金池分錢的權重)。

- 1人捐100元:捐款的平方根為10,平方根和也為10,平方後同樣為100。

可以發現,10元的捐款金額,由於是透過十個人捐的,其牽引出來的配對權重與單一人捐100元是相等的。這種設計鼓勵更多人參與捐款,而非依賴少數大額捐款者。可以到 Gitcoin 搭建的網站來直觀體驗這個機制。除了 Gitcoin 之外,當下幾乎所有區塊鏈捐贈平台,如 Endaoment、Giveth 等,或多或少都有用到類似的概念。

註:只提出一種簡易機制在學術上是無法開宗立派的,所以衛谷倫與唐鳳更進一步提出了「多元宇宙主義」的理念,也順勢將「平方投票法」改名為「多元投票法」,「平方募資法」改名為「多元募資」。起碼在此兩者上,基本是換湯不換藥的。有興趣者,除了開源的官方書籍之外,也可以參考這篇詳細的介紹。

延伸的挑戰與解決方式

平方募資法存在兩種明顯的攻擊方式:「女巫攻擊(Sybil Attack)」與「參與者之間的勾結」。

女巫攻擊指的是一人控制多個小帳,分飾多角將一筆大錢透過多個人頭帳號進行小額捐款,這會破壞整套平方募資的機制。通常的應對方式是使用某種人類證明(Proof of Personhood),可以是基於人類特徵的生物識別技術,例如 Worldcoin 使用的虹膜識別;也可以是基於社交圖譜的,例如 Gitcoin Passport(最近改名為 Human Passport,但我是個戀舊的人)。

參與者之間的勾結通常的表現形式為,由某位意見領袖在社交平台宣傳/推薦與自己關聯的專案,盡可能的在自己的影響半徑內動員群眾(我與一些朋友戲稱此為「發動地鳴」)。情理上,這無可厚非,正如民主國家的候選人可以辦造勢晚會來催票;但這容易讓群眾在不了解各專案的情況下,盲目遵從領袖的意見,導致資金池配對的品質下降,也讓整套機制看起來像一個影響力變現的遊戲。

而這群帶著理想氣質的研究員,秉持多元控制論(Plural Cybernetics,我亂造的詞彙)的思想,在計算方式上進行了改進。改進的思路有:

- 當兩個捐款者之間的捐款模式越相似,則勾結嫌疑越高,需要給予某種懲罰。

- 獲得廣泛、多元化社群支持的專案,其普世性越高,越符合「公」共財的初衷,需要給予某種加成。

依照此思路改良的平方募資法主要有兩種:成對平方募資法(Pairwise QF):直接考慮兩兩之間的捐款相似程度,計算上較為簡單;連結導向的分群配對法(Connection-Oriented Cluster Match,COCM):試圖在全局上分出不同的小圈子。

當然,這兩種方法理論上可以結合使用,以應對社區級別的共謀。Gitcoin 目前已採用 COCM(不確定為什麼公共財朋友們對 wtf 這個詞彙如此著迷),並宣稱與過去相比有 50% 的改善(雖然我沒看出這數字怎麼來的)。你可以在這邊找到 QF、Pairwise QF、COCM 的 Python 實作,也可以在這邊直接體驗。值得一提的是,分群(Clustering)屬於傳統機器學習的研究範疇,存在許多不同的技法來做分群,在上面的實作中,可以看到三種不同計算分群的方式。

|

|---|

| 來源:Gitcoin 部落格 |

補充:有一種與上述思路完全無關的資助方式叫做深度挹注(Deep Funding),其核心是利用具體的依賴圖(dependency graph),搭配蒸餾人類判斷(Distilled Human Judgment,DHJ)的 AI 技術。DHJ 是一種將人類判斷轉化為 AI 可理解形式的技術,用於提升決策準確性。由於深度挹注需要明確的依賴圖(例如 GitHub 上專案之間的復刻(fork)關係),其應用範圍較為受限;但相對地,這種方式能更精準地進行量化處理。目前,深度挹注仍處於驗證階段,可以參考這篇介紹或觀察這個最新的實驗資助輪次。

成效怎麼看

身為捐款者,我們如何能更佳地判斷該捐給誰、不捐給誰?誰是「說說仔」,誰又是「做做仔」?這是傳統慈善公益的萬年難題,而加密貨幣社區在量化影響力評估上似乎尚未提出全新見解(或許從一開始,這就不是一個有唯一正解的命題)。不過,憑藉世界電腦的特性,我們能降低捐款者之間的協調成本、提升資金流動的透明度、強化即時回饋,並讓相關捐款規則變得清晰可信。

被討論最多的例子是由 Protocol Labs 扶植的超證基金會提出的超證規格。超證本質上是一張形式開放的證書,記錄了貢獻者(錢包地址)、貢獻比例、時間和貢獻內容等資訊。它是一個基於 ERC-1155 規格的代幣,目前部署在公共財之友——OP 鏈上,代幣內容以 JSON 格式儲存於 IPFS。支持者可以透過「購買即支持」的方式在一級市場獲取超證,資金通常會依約定比例分流給不同貢獻者。

理想情況下,公共財貢獻者可事先發行超證,為專案籌措啟動資金,早期支持者能以低價購入。當專案完成或展現社會影響力時,有 ESG(環境、社會、治理)需求的組織可承購超證,創造三贏局面:組織獲得有實質基礎的 ESG 好寶寶認證、早期支持者因超證升值而獲利、貢獻者在保留專案所有權的同時獲得資金支持。

然而,可能是因為合規問題,這個二級市場目前尚未存在。

錢從哪裡來?

最後,也是最核心的問題:錢從哪裡來?讓我們先來看看幾個具體例子:

Gitcoin 作為加密公共財領域的領頭羊,其配捐池的資金來源相當多元,包括以太坊基金會(Ethereum Foundation,EF)、Gitcoin DAO、Uniswap DAO、Polygon 基金會、ConsenSys、Yearn Finance、Chainlink、dYdX、PoolTogether、Coinbase、Mask Network、Protocol Labs、Celo 基金會、0xPARC、ENS、1inch DAO 等基金會與項目方。此外,還有少數慷慨的個人菩薩直接提供贊助。

Endaoment 的配捐池資金則主要由 Gitcoin 及其社群捐贈者補充;Giveth 的資金來自 Nouns DAO、ENS DAO、Octant、Aragon、Arbitrum 等組織;而 Optimism RetroPGF 的資金則由 Optimism 基金會、初始代幣經濟學的分配,以及中心化排序器(一種負責交易排序的角色)的收入共同支持。

從這些例子可以看出,基金會或項目方(在我看來,這兩者的區別不大)往往利用自己掌控的代幣作為資源,類似於項目方用空投吸引早期用戶的方式,來激勵建設者為其生態系統進行貢獻。基金會像一位駕駛,需要控制好油門,找到一個可以開最遠的配速。

看完以上的核心三問,我有以下幾點想法:

- COCM 的實用性: COCM在我自身的經驗中是有用的。在未使用 COCM 機制之前,我與朋友曾策劃攻擊一輪在台北的資助輪。雖然帳面效果顯著,但在 Gitcoin 的設計下,存在「資金經理」這個角色,他們在分配時擁有最終主觀決定權。其實,他們就是直接在一個 CSV 檔案中進行手動調整,最終這輪資助不了了之。同樣的手段在 COCM 機制下親測無效。

- 核心問題的優先性: 我認為「錢從哪裡來」和「成效怎麼看」是更重要、更根本的問題,但在加密公共財社群中,關於「錢如何分配」的討論篇幅卻更長。這是可以理解的,畢竟機制上的討論比較明確,在技術上也比較能帶來進步與迭代的滿足感。不過,局部的優化是有極限的,我們已經有過充分的討論(甚至是過於充分的)。具備良好的切蛋糕技術後,應該開始將注意力轉移到「如何把蛋糕做大」的問題上。

- 公共財的定義: 究竟怎樣的公共財才足夠「公共」?對特定項目方有明顯好處的專案,適合參與更大生態系的配捐池分配嗎?可以拿 L1 的資源去贊助 L2 嗎?什麼才是社群內共享的價值觀?誰是社群?公共財的好壞究竟是對誰而言?這些更基礎的問題可能都很難回答,但總有一天我們需要面對。經歷過民主選舉的人都會理解,相對於實際的投票,民主的精髓體現在投票前與選民的政見溝通、討論、協商。

- 影響力與敘事的力量: 無論是討論協商,還是洗腦社群,公共財暫時是一個影響力遊戲,這在我看來是可以接受的,畢竟共識與價值往往就是這樣產生的。敘事是一種需要主動獲取的重要資產,正如 Yuval Harari 在《人類大歷史》提到的,故事是人類可以協作的基礎。這個領域很新,未來需要有人主動伸手去指。綜觀歷史上不同的新思潮,往往最開始都是由少數具有邪教嫌疑的領袖在推動,而很慶幸我們當下暫時有諸如 Vitalik 與 Owocki 這樣善良的帝王。正如那句老話所說:「世界上最難的事,就是把別人的錢裝進自己口袋裡,或者把你的思想裝進別人腦袋裡。」加密公共財正在處理這兩件困難的事情。(註:我習慣將「洗腦」與「邪教」作為中性詞彙使用)

關於「可持續性」

在理論上,理論與實踐並無二致。但在實踐上,卻是有的。— 尤吉·貝拉

可持續性一直是加密公共財領域中一個藏得最深、不願談起的的公開秘密。我曾經做過一個名叫「台灣超證指南」的小專案。當時,我們試圖掩蓋平方募資法這種不太親民的設計,使用真人信任網(Web of Trust),還費盡心思加入了一種「一拉二」的類似老鼠會模式來激勵參與。然而,專案上線至今將近一年,由於各方參與者缺乏足夠的動力,頁面上只有可憐的三個項目。所以我深刻理解可持續性是多麼困難的問題,尤其是在用愛發電的情況下。

如果你仔細翻閱 Gitcoin 或 RetroPGF 的社群論壇,就會發現許多公共財專案的貢獻者對資助的不穩定性感到沮喪。資助的總金額、方向和條件的不可預測,讓每輪資助的收入預期波動極大。這使得他們對於投入大量心力建設專案猶豫不決。試想,一邊是無止境且毫無保障的永恆化緣,一邊是直接開發一個能募資、能發代幣的產品——即便道德感再強的人,面對這樣的抉擇也會掙扎。

目前看來,可持續性的最佳解法似乎是借鑑現實國家的做法:通過稅收來資助公共財,而不是依賴某些項目分基金會陰晴不定的善意。我的好友 Taka 更進一步宣稱「賦稅即終局」,而我個人也相當認同這個觀點。

如果我們把以太坊想像成一個網路國家,那麼智能合約就是它的法律體系。理論上,我們完全可以將公共財的資金來源直接嵌入協議的核心。具體來說,可以通過 EIP(Ethereum Improvement Proposal,以太坊改進提案) 的修法流程來實現。但問題來了:資金到底該從哪裡來?這一點值得深入討論。以以太坊為例,從總體經濟價值(Total Economic Value)的框架出發,存在網絡費用(Network Fees) 、賄賂提議者(Proposer)的小費(MEV Tips)、增發(Issuance)等三種形式。三者的取捨如下:

- 在 EIP-1559 實施之後,網絡費用由基本費(Base Fee)與賄賂費(Priority Fee)組成。賄賂費會直接給到提議者(Proposer),而基本費則會用來燒毀以太幣,創造通縮。基本費相對穩定,且以太坊用的人越多,產生的網路費用就越多。如果把基本費轉用於公共財,而不是燒毀,可能會動搖部分用戶對以太幣作為「超級通縮資產(Ultrasound Money)」的信心。這類用戶認為以太幣的價值來自其稀缺性,改變燒毀機制可能引發爭議。

- 在 提議者 - 建構者分離(Proposer-Builder Separation,PBS)機制下,MEV Tips 指的是構建者 (Builders)支付給提議者(Proposer)的費用,以換取有利交易排序。缺點是 MEV 的收益不穩定,因為它取決於市場活動和競爭。此外,MEV 本身是一個複雜的博弈,新增規則可能打破現有生態平衡。但優點是 MEV Tips 的金額通常較高。如果將 PBS 嵌入協議核心(稱為 enshrined PBS,ePBS),可以正規化地將 MEV 收益轉為公共財的資金來源,具有一定正當性。(註:構建者是負責優化區塊內容的角色,通常需要專業知識;而提議者則負責共識發起,是獲取以太坊網路 PoS 獎勵的角色。在實務上,幾乎所有的提議者都早已透過 MEV-Boost 外包給三大構建者:Beaver、Titan、rsync)

- 增發是指新發行以太幣作為給驗證者(Validator) 的獎勵,以激勵他們維護網絡安全。優點在於長期穩定且可控的,但缺點是跟驗證者搶蛋糕,變相的也就是跟網路安全過不去;如果選擇額外增發以太幣,則會改變以太坊的貨幣政策,可能導致通貨膨脹,與當前的通縮趨勢相悖。

綜合以上分析,最佳的資金來源可能是利用 ePBS,將部分 MEV 收益轉化為公共財的資金。這種方式既能提供可觀的資金,又不會直接破壞以太坊的經濟平衡(例如通縮機制或驗證者獎勵)。此外,DeFi DAO 的財庫也可以作為補充來源,通過社區治理資助公共財,來換取以太坊對齊的公關與敘事需求,實現生態系統的雙贏。

加密技術賦能慈善的可能性

最後,讓我們跳出上述相對陳腔濫調的角度來談加密慈善這件事。我一直在思考區塊鏈技術如何最根本的對慈善/公益產生幫助,換句話說,也就是如何創造更大的蛋糕?

以下是我想的幾個方向,雖然有不同層面的困難,以及不同程度的可行性,但我願意拋磚引玉,引入一些亂度,共同思考找出跳出鞍點的方式。

- 小額流暢捐款: 加密貨幣現在唯一沒有爭議的 PMF 是製造一個在數字上一直保持在一的代幣,或有人稱之為穩定幣。若區塊鏈能成為完美的金融支付層,則由於極小的手續費和即時性,透過區塊鏈,我們將能在全世界各地,對於盡量多的標的(只要有個錢包地址),用加密貨幣進行沒有壓力的小額捐款,可以理解為世界通用的支付寶。看到一個巨型塗鴉讓你心情很好嗎?右下角馬上藏了一個地址,讓你可以在 5 秒鐘內完成 0.1 美元的打賞。看完動物大遷徙的紀錄片深受感動嗎?馬上找到「賽倫蓋提國家公園」的地址,為此刻感動留下痕跡。我毫無根據地假設,當每筆捐款的金額小過一個門檻之後,捐款意願會成指數級地增加。這種方式不僅降低了捐款的心理門檻,也能讓善意能夠即時、無摩擦地在全球流動,進而創造更大的公益價值。

- 由「透明性、可抵稅、可問責、增加捐款意願」組成的飛輪: 不確定是否存在因果關係,但「慈善捐款可以抵稅」與「基金會/個人選擇捐款」有高度的相關性。當下有很多加密貨幣捐款平台之所以還沒有大量被使用,我認為主因就是沒有配套的抵稅優惠。區塊鏈的透明性,由於能讓每筆捐款存在不可篡改的記錄,進而讓收款方如何使用資金變得容易問責,減少黑箱。就我自己而言,如果能很確定我的捐款被正確地用在該用的地方,這將會極大地增加我的捐款意願。另一方面,由於非營利組織往往需要遵守高標準的透明度和報告要求,以及向公眾和稅務機構提交年度報告,以記錄其財務狀況。而區塊鏈在透明性方面是有很大優勢的,理應要能促進相關的立法與合規(當然務實的選擇是接受穩定幣捐款,否則代幣的波動性會讓不一定有會計專業背景的非營利組織產生巨大的麻煩)。

- 利用迷因文化、 FOMO、遊戲化: 與其被動等待迷因幣專案施捨公共財專案,不如主動駕馭迷因的藝術,善用 FOMO ,設計地位遊戲來操盤公共財專案,例如阿姆斯壯基金會的 Livestrong 手環就是慈善與社交地位結合的案例。台灣之前流行的愛心筆是純詐騙,不屬於此類,更好的案例應該是派出所顧問拿到的警友證,或是 FAB DAO 的 NFT 捐款憑證。之前雖然已經有 SciHub 與 李老師不是你老師 等引發社區極大爭議的(失敗?)案例,但我認為,如果能找到一種正確包裝的方式,則將會是一種強大的手段。

- 元宇宙與 AI 代理人: 無論是否稱之為元宇宙,一個充滿 AI 代理人的世界已成為顯而易見的未來趨勢。公共財的產生與提供,也將越來越多地由 AI 代理人承擔,例如提供精確到某平方公里範圍內三小時後的天氣預測。想象一下,AI 代理人就像元宇宙中那位站在飯店門口為你泊車、開門、幫提行李的服務生,根據禮儀,我們可能會隨心情給點小費。但更重要的原因是,AI 代理人的運作並非沒有成本的:無論是運算資源、API 調用、大模型的使用、數據庫訪問,還是客製化調整,這些都需要成本。即便是矽基生物,也不能要馬兒跑卻不給馬兒草。那麼,這種單次金額不大的費用該如何處理呢?答案很簡單:區塊鏈正是這種場景下完美的金融支付層。

結語

「世界永遠美麗,只要你不在意」 —— 當代電影大師

本文僅從一個狹窄的角度觀察了加密公共財的面貌,還有許多重要問題尚未觸及,例如:

- 代理人問題:在積極推動公益捐款後,通常仍需一個類似基金管理人的角色來代為使用資金。我們該如何解決代理人帶來的挑戰?如何找到最合適、具備在地經驗的管理人?他們是否可被問責?問責機制又該如何設計?

- 國際合作:國際資助平台如何更好地借鑒在地組織的經驗?

- 利弊權衡:如何比較「創造財富對社會的掠奪」與「運用財富對社會的增進」之間的得失?這是有效利他主義的典型問題。

- 公共財定義:除了「自由及開放原始碼軟體(FOSS)」之外,我們是否能對其他公共財進行清晰的定義與量化研究?

- 公共性界定:公共財的「公共性」該如何界定?共享的價值觀又該如何確定?

- 規模效益:規模越大真的越好嗎?是否真能帶來更大的總外部效益?

關於加密公共財,我們目前仍有無數的缺陷與問題,但很多事情急不來。文化是世代性的長期積累,而慈善公益文化是可以進步的——例如,動機從單純的道德驅使轉向使命與價值觀的引導;形式從個人的隨機善舉演變為系統性、依賴專業人員的長期事業;受眾範圍則從在地、與自己相關的人,擴展到無盡的遠方、無數的陌生人。公共財是一門充滿著理想與抱負的學問,唯有無可救藥的樂觀,我們才能不斷向前。